Based on recent leaks, Chinese cyber mercenaries may be more like the NSO’s and Hacking Teams of the world than previously expected. On February 16, 2024, a set of internal documents, chat logs, and sales pitches seemingly belonging to Chinese security contractor Shanghai Anxun Information Co. (上海安洵信息公司) “i-Soon'' were leaked onto code-sharing site Github.

Plenty of cyber threat intelligence firms have covered the leak’s tools, i-Soon’s relationship to Chinese threat actor APT41 (and affiliated cyber mercenary firm, Chengdu 404), as well as i-Soon’s wide number of clients. However, this trove of documents also reveals plenty about China’s offensive cyber capability industry: how they are surprisingly similar to their Western counterparts, but different in other important ways.

Why does this matter?

Countering the proliferation of offensive cyber capabilities has been a priority item for the US, UK, France, and other partners since the Summit for Democracy in 2023. While the world has focused on NSO Group and other firms out of Israel, this is a global market for capabilities, and China is a key adversary in cyberspace. Prior to this leak, little has been made public about the Chinese offensive cyber capability marketplace, or its relationship with the wider East Asian region.

Moreover, the insights gleaned from the i-Soon leak could not have come at a better time: the 2024 Summit for Democracy, which is expected to have further news about international efforts to combat spyware and other offensive tools, is being held in Korea, and will have plenty of attendees from the region. China has consistently been an elephant in the room with regards to these discussions, and this leak enables policymakers to understand how trying to curb the marketplace will affect Chinese offensive efforts, as well as those of our East Asian partners and allies.

Key Findings

- The Chinese government specifically contracts out hack-for-hire work: contracting documents between i-Soon and both military and law enforcement show specific requests for Gmail and other target email contents – requiring i-Soon to actively break into mail servers and pull content for their government customers.

- Antivirus firm Qihoo360 invests in cyber mercenaries and may be selling them user PII: China’s largest antivirus firm, Qihoo360, is an investor of offensive capabilities firms and may be selling PII of individual antivirus customers to an offensive company it funds that does intelligence work for government clients.

- Tianfu Cup confirmed to be exploit feeder system: the Tianfu Cup is confirmed by the leaks to likely be a vulnerability feeder system for the Chinese Ministry of Public Security (MPS). When proof-of-concept vulnerabilities submitted to Tianfu aren’t already full exploit chains (ready to use), the Ministry of Public Security disseminates the proof-of-concept code to private firms to further exploit.

- Naming and shaming has mixed market results: Naming and shaming individual companies in the space can have the opposite effect, and even be used as marketing by certain threat groups. However, indictments can also cause employees to leave those companies to find other work (albeit at other similar firms).

- Chinese firms have a well established Capture-the-Flag to hiring pipeline for offensive talent: i-Soon, a company of around 100 employees, partners with provincial ministries of education (equivalent to state-level departments of education in the US) and defense contractors to put on capture-the-flag competitions to attract talent. One of China’s most well-known offensive security teams, Pangu Team, is a subsidiary of a large prime defense contractor, Qi Anxin.

- Well-funded, prime/sub-contracting ecosystem: Like their Western counterparts, Chinese offensive capabilities firms are large, sometimes venture-backed firms in a dense ecosystem of players. Some firms directly bid for Chinese government contracts, some work with large prime contractors, and some join forces with other small firms to partner on contracts together. Unlike the West, however, small Chinese firms will often offer entire suites of services, ranging from threat intelligence to reconnaissance tools, and even actual hack-for-hire services.

Recommendations

- Elevate the i-Soon revelations in cyber capabilities proliferation dialogues, like at the Summit for Democracy in March 2024, hosted in Korea: these revelations showcase that China contracts private firms to hack into organizations worldwide, including in Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, the U.K., and India. The U.S. and its partners can use these leaks to bring new partners on board.

- Promote alternatives to vulnerability hoarding: while China is using a vulnerability hoarding or “buggy bank” strategy to amass power in cyberspace, hoarding vulnerabilities inherently leaves the global internet ecosystem less secure. The U.S. and its partners should advocate for responsible vulnerability disclosure and Vulnerability Equities Process-like systems, and provide guidance to partners and allies on how to create these processes.

- Create norms against private sector hacking: Governments should create ways to ensure better delineation between civilian and combatant cyber forces in event of a conflict. Moreover, if large technology firms can attribute exploitation of their products to iSoon or other Chinese technology firms, they should consider suing them in U.S. courts, as done in Whatsapp v. NSO.

- Further encourage international sanctions on Qihoo360 and other Chinese firms: The U.S. government already added Qihoo360 to the entity list in 2020. The U.S. and its partners should use the revelations from the leak to encourage partners to also sanction the company, while preventing allied government employees from downloading the application.

- Follow individuals, rather than companies: The U.S. and its partners should apply people-centric policies to the offensive cyber proliferation space. Governments can indict particularly egregious founders (like the founders of Qi Anxin and Qihoo360) and offer employment visas to exceptional foreign engineers—both options take key staff away from foreign companies.

- Partner with CTF teams to develop cyber security talent: While US government efforts focus on universities, few partner with or fund CTF teams. Larger private institutions should consider funding additional CTFs like CSAW or individual CTF teams that help organize such competitions, and consider facilitating safe spaces for international research collaboration.

Introduction: Offensive Cyber Capabilities, the Chinese Market, and i-Soon’s Place within it

An offensive cyber operation needs four things: 1) initial access into a target environment, 2) malware to put in that environment, 3) a way to talk to the malware (like a command-and-control server), 4) someone trained to conduct the operation.[1] Many of these individual capabilities can (and are) developed in the private sector: in fact, some companies sell all these components together, offering “Access-as-a-Service" to government clients. Because these capabilities are all expensive to develop and retain in house, governments increasingly rely on private companies to bolster (or even completely supply) their operations: NSO Group, an Israeli cyber mercenary firm, is linked to providing services to multiple governments; even the FBI had to rely on a private Australian firm to break into the San Bernardino shooter’s iPhone post Apple v. FBI dispute.

The Western hacking community has origins stemming from counterculture like phone phreaking and loose online bulletin board systems, as well as an originally fraught relationship with law enforcement and large technology firms. Chinese hacking communities, on the other hand, came out of patriotism. Many of the original patriotic hackers from the 2001 US/Sino Hacker War, who defaced US websites after a US spy plane collided with a Chinese fighter jet in the South China sea, are now executives and senior engineers at some of China’s largest technology and cyber security companies. The most famous of these is Tan Dailin, or “Wicked Rose” - once a Sichuan University of Science and Engineering student carrying out DDoS attacks against DOD websites in 2006, Tan was named in the 2020 FBI indictment against APT41, which claimed that Tan worked with Chengdu 404’s Vice President at an “offensive hacking group” with relationships to government agencies. Both individuals were charged with conspiracy and CFAA violations.

As the global cyber mercenary ecosystem has exploded in the last twenty years, China’s ecosystem has been no different. China’s Tianfu cup is a prime example of this – a hacking competition hosted in China by some of China’s most famous cybersecurity companies and institutes.[2] Hacking competitions like Tianfu cup, as well as other more offensive “capture-the-flag" (CTF) competitions, showcase some of the world's best offensive hacking talent. To be clear, i-Soon does not have the capabilities to compete in a Tianfu Cup-like competition on their own - in the words of one of their engineers in 2022, there are only 4-5 people in their department who are capable of infiltration.[3] However, they sell malware to Chinese government clients, work with vulnerability brokers, and actively conduct cyber intrusions on behalf of the Chinese government – IP addresses mentioned in i-Soon employee chatlogs are linked to Chinese hacking operations conducted during that timeframe. This company is not a premier hacking shop, but they have useful visibility into the wider Chinese offensive security community.

Same: Private cyber mercenaries are large, sometimes venture-backed, firms in a dense ecosystem

Private sector hackers are not script kiddies in basements: they are businesses with product lines and ample funding. Offensive cyber capabilities are sold by companies – companies with investors, employees, and competitors. Western firms range in size from small private organizations to large defense contractors – NSO Group was reported to have around 700 employees as of 2022. China seems to be no different: chatlogs between i-Soon’s two co-founders, Jesse Chen (lengmo) and Wu Haibo (Shutd0wn) explicitly compare their employees (they have around a hundred) to the thousands employed by Huawei and Qi Anxin – two Chinese cyber security firms. The i-Soon leaked employee rosters add up to around 130 unique names.

I-Soon co-founders compare their sizes to that of Huawei and Qi Anxin within the cyber security market

i-Soon received angel investment from Yongzhou Venture Capital in 2016 and received Series A funding from CASH Capital and Qihoo 360 in 2018.[4] The i-Soon co-founders have also discussed future Series B rounds, potential contacts to take them public, and revenue numbers. In 2021, the CEO claimed that i-Soon’s revenue reached 70 million yuan (9.7 million US dollars), with expectations to double their revenue in 2022.5

The relationship between i-Soon and Qihoo 360 –– a Chinese antivirus firm placed on the US entity list in 2020 for its ties to the Chinese military, is particularly interesting: leaked conversations between two i-Soon senior employees state that i-Soon can purchase data from 360 to cross compare QQ accounts with MAC addresses and other data to find the real identities of individuals they target, with mixed success rates.

The conversation’s context involves virtual identity - which is a service “under development” based on iSoon’s Skywalker Data Query platform sales documentation: “a dedicated confidential application system that provides real-time query for target logistics information and network virtual identity information.”[5] The virtual identity service would enable a user, after querying a target person, to be able to retrieve the target’s internet “virtual identity” based on query keywords, including QQ and WeChat data. This querying feature works in the opposite direction as the resource gathering method mentioned in the chatlogs, but it is possible that the data gathering is done on the back end prior to user query. If the Qihoo360 data is being used in this way, the antivirus firm would be selling (either formally or informally) PII of individual antivirus customers (real names, for example, alongside their device MAC address) to an offensive company it funds, so the company (iSoon) can find people based on their online activity and hand their identities to government clients.

Skywalker Platform “Virtual Identity Query” (Under Development)

I-Soon leaked chatlogs (original, translated) of two senior employees

When it comes to talent, the two co-founders also frequently talk about their industry partners (who occasionally steal their talent, and vice versa). In 2020, when the FBI named Chengdu 404 in an indictment, the iSoon co-founders implied that they were drinking buddies with many of the indicted individuals. While the iSoon co-founders assure each other that they have no public link to Chengdu 404 at the time, they became embroiled in a public intellectual property dispute with the company in 2023. Later on, one of Chengdu 404’s researchers sent their resume to i-Soon. While the FBI’s naming and shaming techniques may be ineffective against certain individuals, (and are even used as marketing by the groups themselves) some employees can still be swayed to leave firms that are conducting criminal activity in cyberspace - albeit to go to other firms doing similar work.

I-Soon co-founders discussing the APT41 Indictment

Same: Prime / Subcontractor markets

Companies that provide services or products to governments – even when dealing with offensive cyber capabilities, largely use government contracts. Some of the West’s most elite offensive security groups attempt to directly bid for contracts. However, because government contracting is slow and difficult, many end up becoming subcontractors for or get fully acquired by large prime contractors. Moreover, when companies can’t provide all portions of an offensive cyber capability, they themselves will contract out that work to a subcontractor.

These dynamics are also easily identified in the i-Soon leaks. Chatlogs between i-Soon’s two co-founders, Jesse Chen (lengmo) and Wu Haibo (Shutd0wn), as well as between other employees, mention companies that act as suppliers, primes, investors, competitors, and even a combination of all four.

Chatlog (original, translated) of i-Soon’s relationships with contractors and the government

One standout example is i-Soon’s relationship with NoSugarTech (无糖信息, or 无糖 ). NoSugarTech (nosugar[.]tech) is a startup in Chengdu funded by the venture arm of Qihoo360, Gaocheng Capital, and other large firms. They advertise “cybercrime combatting” technology, which includes vulnerability research, as well as other offensive and defensive tools. According to the chatlogs, NoSugarTech is both subcontractor and competitor to i-Soon - NoSugarTech provided a QQ vulnerability to i-Soon on a pay-per-use basis, is on contracts with i-Soon, and recruits researchers from the same talent pools.

Selection of chat logs (translated) between i-Soon’s co-founders about their relationship with NoSugarTech

As for larger firms, Qi Anxin (qianxin[.]com) seems to be i-Soon’s prime contractor, competitor and potential investor. Qi Anxin is a large cyber security firm and defense contractor, publicly traded on the Shanghai Stock Exchange. According to the same chatlogs, i-Soon has relied on investment funds from Qi Anxin to pay their departments, and has considered cooperation with the large contractor to help provide training to other clients. These conversations suggest a prime-sub contractor relationship, whereby a large company like Qi Anxin procures government contracts and relies on smaller companies like i-Soon to fill in gaps within its capabilities. Qi Anxin is also the parent company of Pangu Team/Pwnzen Infotech – a cybersecurity research team well-known globally for mobile exploitation.

Selection of chat logs (translated) between i-Soon’s co-founders about their relationship with Qi Anxin

Different: Information operations, threat intelligence, reconnaissance, and hack-for-hire services can all be provided by a single Chinese firm

Aside from prime contractors, Western firms are deeply unlikely to offer threat intelligence, information operation capabilities, reconnaissance capabilities, and offensive cyber capabilities at the same time. While some firms may offer a defensive tooling suite to pay the bills (exploitation contracts tend to be more erratic in nature), offering more than 2-3 different verticals is difficult for a small firm.6 I-Soon offers all these capabilities – likely to gain market share and diversify streams of unstable income. In addition, most countries do not encourage hackers-for-hire: authorizing private actors to hack into systems creates risk of unintended escalation and encourages private activity that is illegal under most other circumstances. The International Committee of the Red Cross has even called civilians engaging in this activity as a worrying trend, especially if the activity continues into a wartime environment. i-Soon, however, directly steals from targets and gains access to target computers for both the Chinese governments’ spy and law enforcement agencies - because the Chinese government specifically contracts this work out to private companies.

Based on the leaked chat logs and sales pitches, i-Soon offers intelligence (QB - 情报) products, trainings via an “Anhui Academy”, special reconnaissance services (the likely meaning of TZ - tèwù zhēnchá 特务侦察), and clearly break into systems themselves. They are effectively a malware, surveillance, threat intelligence, and a hack-for-hire firm combined – although based on disgruntled employee complaints in the leaks, they provide these services with varying degrees of quality.

I-Soon's own pitch deck brands itself as a “TZ'' firm: “committed to providing comprehensive solutions for TZ product research and development, TZ capability technical services, and TZ talent cultivation, and contributing [i-Soon’s] strength to public security customers in the direction of cyberspace confrontation, equipment construction, intelligence acquisition, and talent cultivation. Its product lists are largely remote access trojans (远端控制管理 is a form of remote desktop software). However, the products list also includes social media monitoring, penetration testing tools, anonymous communications networks, and trainings for all its products.

I-Soon leaked marketing material and selection of products list

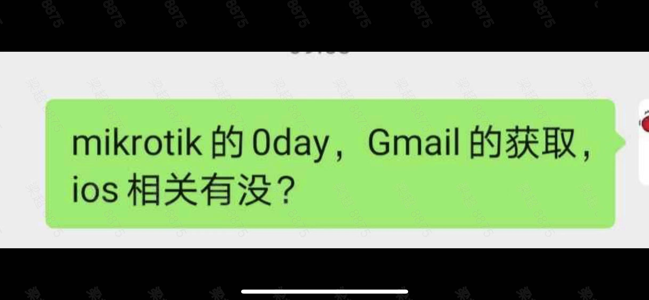

Moreover, China does not care about preventing private actors from conducting operations as long as they’re sanctioned – in fact, they explicitly request these services through its government contracts. The i-Soon leaks show that customer contract requirements for the Hubei branch of the People’s Liberation Army, as well as those for the Haikou Public Security Bureau, specifically request that i-Soon pull victim mailbox contents on a regular basis to deliver to customers. The leaks also contain screenshots of i-Soon employees chatting about getting access to mail servers in real-time.

Selection of translated contracts from i-Soon’s Sichuan branch

Screenshot of i-Soon employees chatting about getting access into a target mail server (Original and Translated)

Different: Proliferating Vulnerabilities between firms and the Chinese Provincial Government through the Tianfu Cup

Vulnerability research and exploitation is key in offensive cyber operations: if the intended target of an intelligence operation has fully patched systems, an exploit chain (code exploiting a series of vulnerabilities in software) usually involving a zero-day vulnerability (a software vulnerability with no known patch, i.e. 0day) will likely be required to gain access. However, getting from vulnerability to exploit is not easy: vulnerability proof-of-concept code may not fully work, or simply cause the software to crash instead of enabling exploitation. Moreover, with modern software, multiple exploited vulnerabilities (called “exploit primitives”) may need to be chained together to get worthwhile access into a system.

These struggles can be seen in competitions like Tianfu Cup and Pwn2Own: some teams submit code that does not fully work, or successfully demo single bugs, while others may chain multiple single exploit primitives together. In 2021, Tianfu Cup reported 30 successful demonstrations exploiting new vulnerabilities in US software products, including Windows 10, Apple iOS, Safari, and Chrome. This was 40% more than the number of successful demonstrations at the equivalent international competition with U.S. turnout (Pwn2Own) that same year. Moreover, the patriotic relationship between hackers and the Chinese government almost seemed so strong they could read each other's minds: one of the Tianfu Cup vulnerabilities was subsequently “found or replicated” in Chinese cyber espionage campaigns targeting the Uighur population.

Based on the i-Soon leaks, one can draw three conclusions: first, that the Chinese Ministry of Public Security Departments are indeed getting access to exploits found by private companies during the Tianfu Cup; second, when the Tianfu Cup submissions aren’t already full exploit chains, the Ministry of Public Security disseminates the proof of concept vulnerabilities to private firms to further exploit these proof-of-concept capabilities; and third, provincial departments work with cities and prefectures to break into their desired target sets. This vulnerability feeder system even precedes China’s vulnerability disclosure requirements, which push companies and researchers to disclose software bugs to the Ministry of Public Security and Chinese Ministry of State Security (MSS). The i-Soon chatlogs suggest that China’s vulnerability disclosure requirement is one part of the puzzle of how China stockpiles and weaponizes vulnerabilities, setting in stone the surreptitious collection offered by Tianfu Cup in previous years.

As stated above, i-Soon does not have the talent to compete in a Tianfu Cup-like competition on their own. In their own operations, they rely partially on vulnerabilities provided by NoSugarTech and other firms. While i-Soon does not have a fleet of vulnerability experts, the company is clearly plugged into the Chinese provincial vulnerability ecosystem. Their prime contractor, Qi Anxin, helps organize the Tianfu Cup. Moreover, the below two chatlogs show the two co-founders chatting about the Tianfu Cup, claiming that the Ministry of Public Security obtained the proof-of-concept code (POCs) for the vulnerabilities submitted at the Tianfu Cup, and then disseminated them to the Jiangsu provincial department. The i-Soon founders were able to ask their contacts where the POCs were disseminated, only to find they were given to the Wuxi City Public Security Branch. The founders also mention the difficulty of exploiting certain kinds of vulnerabilities (like ones belonging to Apple iOS). They further state that the Ministry of Public Security will disseminate vulnerabilities to Jiangsu and other “strong provinces” every year.

i-Soon co-founders talking about Tianfu Cup

The founders then pivoted their conversation about Tianfu Cup vulnerabilities into the wider vulnerability ecosystem within China’s Ministry of Public Security, stating that the larger provincial offices tend to either give out vulnerability tools, or request a list of targets from the prefecture and city branches, subsequently get access to the targets, and hand the access back to the lower branch. The city and prefectures are also able to give “semi-finished” vulnerabilities to offensive companies to try to exploit: the CEO compares the process to a “group writing assignment”. The chat logs also bear similarities to a claim made in the 2021 DOJ indictment against Ministry of State Security front company Hainan Xiandun, where provincial Ministry of State Security officers provided malware and vulnerability evaluation to the company for use against foreign government targets. This almost collaborative process is deeply unlike a traditional government contractor relationship when it comes to the exploit marketplace in the West.

i-Soon co-founders talking about Provinces and Vulnerability Dissemination

Same: The CTF to offensive talent pipeline - talent, tooling and training issues

Pwn2Own or Tianfu Cup aren’t the only computer hacking contests around. Most hacking contests revolve around a Capture-the-Flag model (CTF), where teams solve challenges by hacking into systems – if the system is successfully exploited, the participant will find a “flag”, which can be submitted for points. The most famous of these contests is the DEF CON capture the flag – an active attack-defend competition held at one of the world’s most famous hacker conventions, in which teams must exploit other teams’ systems for flags while also patching (protecting) their own. It is an open secret that some of the world’s best talent competes at the DEF CON CTF, and many organizations have realized that running CTFs are incredible talent building and recruiting tools. PicoCTF, for example, is a well known CTF organized by Carnegie Mellon University, while CSAW is run out of New York University. Hack The Box is a well-known upskilling organization that uses capture-the-flags as training. Even Google runs its own CTF. Many CTF teams originate from universities, and continue to compete as loose professional organizations when the students graduate and move into the offensive security space.

i-Soon is also well placed in the country’s offensive talent pipeline and CTF ecosystem. It is no coincidence that i-Soon is headquartered in Chengdu – it is a city well known for having plenty of offensive security talent. Like other Western firms, i-Soon partners with universities to organize CTFs, in order to cultivate and attract talent. Their “Anxun Cup” program partnered with the Chengdu University of Information Technology in 2020 - a school closely linked to Chengdu 404 and other APT41 hackers. The Anxun Cup was also run under the guidance of the Cyberspace Affairs Office of the Sichuan Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of China, and the Sichuan Provincial Ministry of Public Security Department. In a university bulletin, Chengdu University of Information Technology advertised that the competition aims "to fully implement the spirit of a series of important instructions issued by General Secretary Xi Jinping on network security and informatization work, to recruit and train special talents in the field of network information, and to enhance the national and provincial network space."

In 2023, the latest iteration of the Anxun Cup, i-Soon partnered with Syclover – a CTF team originating from Chengdu University of Information Technology, a loose collection of students and industry professionals like their Western counterparts. That iteration of the Anxun Cup was open to all of China and included cash prizes of up to 5000 yuan.

I-Soon also seems to have asked Qi Anxin and Pangu for help to develop Android related challenges for the 2020 Anxun cup – suggesting that the two organizations have a more informal relationship than that of a prime and subcontractor.

I-Soon's co-founders talking about the Anxun Cup and Pangu Team’s role

Conclusion and Recommendations

A set of leaked documents making oblique references to the wider offensive cyber ecosystem is not a perfectly reliable source – the revelations from the i-Soon leak should be taken as they are: internal industry viewpoints and sales pitches from a single offensive security company. However, they still enable both researchers and policymakers a window into an otherwise opaque industry, in an even more opaque region of the world. Based on these revelations, policymakers in the public, private, and non-profit sectors should consider the following options:

- Elevate the i-Soon revelations in cyber capabilities proliferation dialogues: these revelations showcase that China contracts private firms to hack into organizations worldwide, including in Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, the U.K., and India. Many of these countries’ governments will be at the 2024 Summit for Democracy held in Korea: the U.S. and its partners in countering proliferation have an opportunity to use these leaks to bring new partners on board.

- Promote alternatives to vulnerability hoarding: it is clear that China is using a vulnerability hoarding or “buggy bank” strategy to amass power in cyberspace. However, hoarding vulnerabilities inherently leaves the global internet ecosystem less secure, not more. The U.S. and its partners should advocate for responsible vulnerability disclosure and Vulnerability Equities Process-like systems, and provide guidance to partners and allies on how to create these processes.

- Create norms against private sector hacking: private firms like i-Soon that hack on behalf of a nation state may create escalation issues in cyberspace, especially considering that i-Soon is gaining access into systems on behalf of the Chinese armed forces. Governments should create ways to ensure better delineation between civilian and combatant cyber forces in event of a conflict. Moreover, these firms are exploiting software belonging to large Western companies to harm users for profit, and currently cannot claim sovereign immunity in U.S. courts. If large technology firms can attribute exploitation of their products to i-Soon or other Chinese technology firms, they should consider suing them in U.S. courts, similarly to the Whatsapp v. NSO and Apple v. NSO cases.

- Further encourage international sanctions on Qihoo360 and other Chinese firms: Like Huawei and Kaspersky Labs, China’s largest antivirus firm has clear links to an adversary’s offensive cyber community. The U.S. government already added the Qihoo360 to the entity list in 2020. The U.S. and its partners should use the revelations from the leak to encourage partners to also sanction the company, while preventing allied government employees from downloading the application.

- Follow individuals, rather than companies: while companies can fade into obscurity, people in the offensive cyber industry largely stay the same. The U.S. and its partners should apply people-centric policies to the offensive cyber proliferation space. Governments can indict particularly egregious founders (like the founders of Qi Anxin and Qihoo360) and offer employment visas to exceptional foreign engineers—both options take key staff away from foreign cyber mercenary companies.

- Partner with CTF teams to develop cyber security talent: One thing the Chinese government does well in this space is partner with its best offensive security teams to recruit new talent. While US government efforts focus on universities, few partner with or fund CTF teams. Larger private institutions should consider funding additional CTFs like CSAW or individual CTF teams that help organize such competitions.

These recommendations and insights only scratch the full surface of what the i-Soon leaks have to offer. This author looks forward to other analysis and policymaking based on the primary source data and these insights.

Special thanks to Kieran Green for his assistance on this project.

Footnotes

[1] That individual likely needs a manager to set operational policies, as well – the fifth factor in the linked Access-as-a-Service piece.

[2] As of this writing, the organizers are Chengdu Tianfu New Area Investment Group, QiAnXin, Cyber Kunlun, Huawei, Baidu, Alibaba, Qihoo 360, NSFocus, Topsec, VenusTech, Tsinghua University’s Institute for Network Security and Cyberspace, AsiaInfo Security Technologies, IntegrityTech, CICS-CERT (i.e. China’s National Industrial Information Security Development Research Center), and Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Information Engineering.

[3] 2022-03-15 16:03:36,wxid_kbys0kvzj4ta12,wxid_icges6alg8cl21,现在我这部门做渗透的有能力的就4-5个人 (i-Soon leak – 40.md)

[4] i-Soon's leaked pitch deck claims that they completed a series A VC Round in September 2018 and Angel financing in 2016 – Pitchbook lists the three investors on i-Soon’s company Pitchbook page.

[5] (i-Soon leak – 12756724-394c-4576-b373-7c53f1abbd94_43.png)