Recently, Margin published a piece on China’s cyber militias and how they fit into their broader defense strategy. It’s gotten a very positive reception overall, but there’s one question that’s come up more than once, both in chats I’ve had and in other corners of the internet: what exactly is a “cyber militia” and what makes China’s cyber militia system unique?

The question is a fair one. As a few commentators have pointed out, plenty of states have cozy relationships between their respective tech sectors and military/intelligence services. So why are we singling out the PRC?

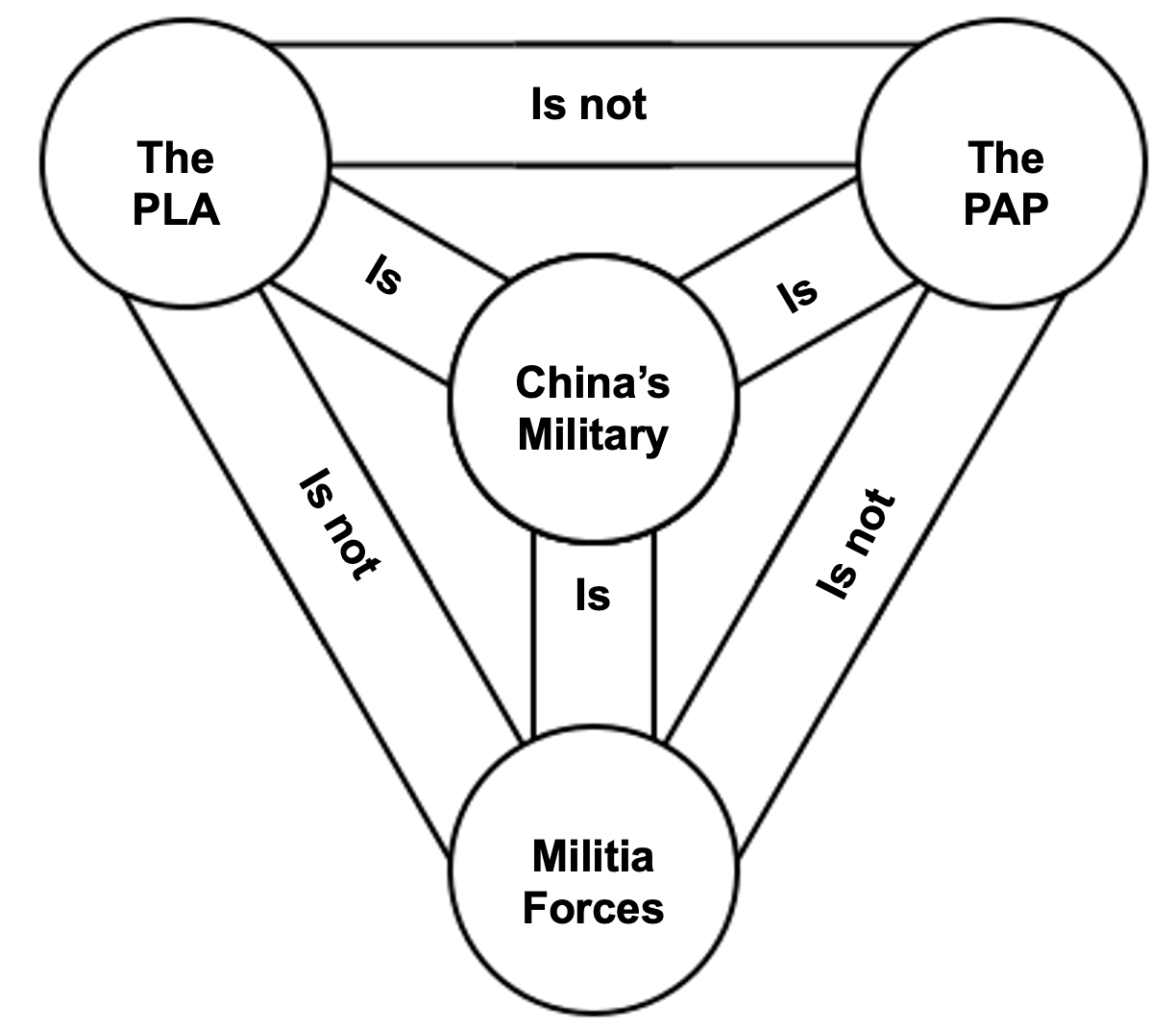

tl;dr in China “militias” are a distinct, legally codified force category that constitutes one part of China’s military trinity alongside the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and People’s Armed Police (PAP).

There are a few things that set China’s model apart.

- First, cyber militia units in China aren’t just a collection of civilian contractors pulled in on a case by case basis for their technical expertise. The people in them wear uniforms. They train. They operate like actual soldiers.

- Second, these militia units are organized collectively through “work units,” or danwei (单位), which is an administrative term used to describe individual entities like companies, universities, and other state-affiliated organizations (we’ll explain the significance of that in a bit).

- Third, cyber operations make up only a small slice of what China’s militia forces actually do. These units take on a wide range of responsibilities, many of which have nothing to do with computers (we’ll get to that too).

Beyond those surface-level bullet points, the militia’s role in China’s defense structure is worth examining on its own. Partly because (in my obviously biased opinion) the frankly byzantine structure of China’s militia system is fascinating in its own right. But also because it reveals a lot about the PRC’s strategic culture, and how cyberspace is viewed as one tool in a rather large toolbox of national power, contrasted with how the US generally utilizes cyber as a stand-alone capacity.

A lot of that background didn’t make it into the final paper. Some of it got buried in footnotes, some of it got cut because the thing was already pushing 50 pages. But I actually think that’s for the best. It gives me a chance to lay it out here in plain terms, for folks who don’t spend an unreasonable amount of their lives poring over back issues of PLA Daily. Just as importantly, it gives me a second bite at the apple to talk a bit more about these (honestly fascinating!) weird little guys and the system they inhabit.

A Very Short and Comically Oversimplified History of China’s Militia System

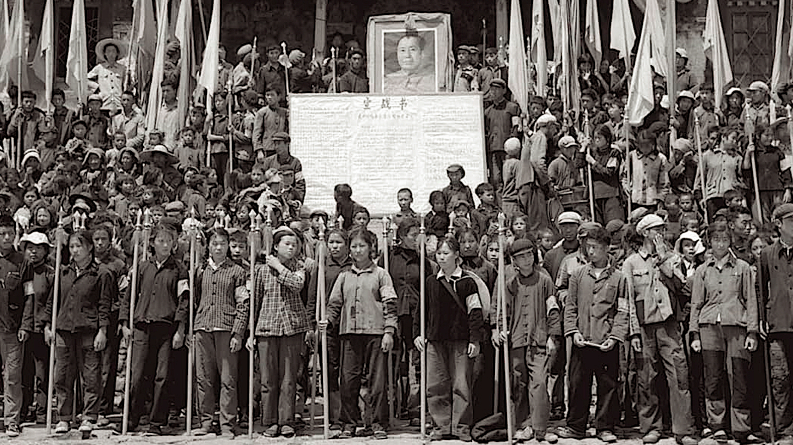

To understand how China ended up with its current militia system you’ve got to rewind to 1949. The CCP had just taken power after a brutal civil war, the country was exhausted, and the leadership needed more than just a professional army. They were staring down the U.S. military across the Korean peninsula, bracing for a possible counterattack from the Taiwan-based Kuomintang, and trying to keep society ideologically engaged. The solution was the militia: local armed groups tied directly to Party structures, made up of civilians with day jobs, ready to be mass-mobilized in a “People’s War” to bog down an invading force.

By the mid-1950s, the system got more structured. Militia forces were brought under a national framework (the “People’s Armed Forces” system) and managed through local People’s Armed Forces Departments (PAFDs) embedded in city and county governments. Now they had uniforms, training quotas, paperwork, and a direct bureaucratic tether to the PLA. That whole setup, to put it mildly, went off the rails during the national psychotic break that was the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution, when militia units stopped being auxiliary defense forces and started picking sides in inter-factional disputes, which often escalated into full-on street fights and (in some cases) borderline localized civil war. Nonetheless, after Mao’s death his successor Deng Xiaoping shifted the country back toward something resembling professional governance, and the militia system was reined in.

From the 1980s on, militias became more practical: disaster relief, logistics, communications, constituting a standing pool of manpower the PLA could tap as needed by way of local PAFD offices. That model hasn’t disappeared — it’s just been updated. Sure, there are still guys conducting civil air defense drills. But there are also university detachments running cybersecurity drills and ISPs tasked with supporting comms infrastructure in wartime.

Wait, Back Up… What Do We Actually Mean by “Militia”?

Let’s start with some modern terms and definitions. Obviously, the word “militia” carries some baggage in the West and brings to mind either a bunch of guys in camo running drills in the woods of Idaho or armed fighters riding around in a Toyota Hilux somewhere in the Syrian desert. But in the context of the PRC, that’s absolutely not what we’re talking about.

In China, the term “militia” (minbing, 民兵) refers to a legally defined component of the country’s national defense system. Militia members are people that have civilian day jobs but are registered, trained, and managed as part of a standing military reserve. Crucially, you generally don’t join the militia as an individual. Rather, you’re organized through your danwei (单位), or work unit. That might be your employer, your university, or your local government department.

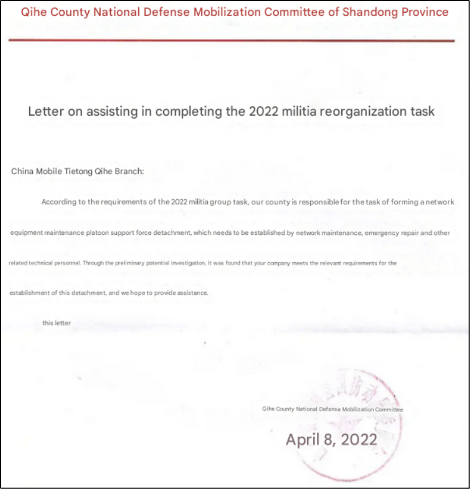

In modern China, danwei are bureaucratic holdovers from a time when the state managed every corner of daily life. During the Mao era, your danwei wasn’t just your employer; it was your housing authority, your food source, and your gatekeeper to everything from healthcare to marriage. Most of those roles faded as China began reforming its economy in the 1980s, but the bones of that framework remain, especially in government-linked sectors. Importantly, danwei still serve real functions in the present day. One thing they continue to do extremely well is feed people into the militia recruitment pipeline. If a local government needs to raise a militia unit, it doesn’t post a job ad. It reaches out to the work units in its jurisdiction and leans on them to contribute personnel to the force.

Once a danwei is tapped, personnel are organized into fendui (分队), or detachments which are the core operational units of the local militia. These are typically structured by technical function. So for example, a university with a strong cybersecurity program might be tasked with standing up a “specialized technical detachment unit” (zhuanye jishu minbing, 专业技术分队) responsible for tasks like cyber operations or communications support, depending on the specific needs of the host region.

These detachments don’t operate in a vacuum. They train and coordinate alongside other specialized militia units such as those focused on logistics, transportation, emergency engineering, or UAV support. The idea is to build an integrated force that can be mobilized quickly and slotted into a larger joint operation, depending on the scenario.

The connective tissue here is the local PAFD office, which is embedded in the civilian government apparatus and oversees militia construction and coordination. These PAFD offices report upward into China’s Theater Command system (the PLA has five Theater Commands, each responsible for planning and conducting joint operations across a particular strategic direction e.g., Eastern, Western, Southern, etc.). So when a local PAFD stands up a militia unit, it’s not just a local affair; it’s building capacity that slots into the operational planning of the PLA writ large.

Okay, But Isn’t This Just the Chinese Version of the National Guard?

At first glance, sure. China’s militia does a lot of the same things as the U.S. National Guard. They respond to natural disasters, support the active-duty military, and help with domestic emergencies. But the resemblance ends there. The key difference is structural. Because these units are organized through danwei, form dictates function. And that form is very different from the U.S. model.

In China, militia units aren’t built out of individual volunteers. They’re built out of work units. The result is a system where the Party-state doesn’t just get raw recruits. It gets pre-packaged functionality. Need cyber teams to protect networks around a critical port facility without pulling uniformed PLA troops off other assignments? There’s probably a nearby network security company that could be induced to stand up a cyber militia unit for the right combination of financial incentives and preferential treatment. Need rear-area comms to stay online in a wartime contingency? China Telecom is right there (and it’s not like they’re going to refuse, given the state subsidies they receive). In other words, it’s conscription by bureaucratic fiat.

And unlike in the U.S. or Russia, there’s no attempt to keep these associations quiet. U.S. contractors supporting CYBERCOM don’t advertise it. Russian criminal groups might work for the GRU, but always with (im)plausible deniability. In China? Militia detachments will literally pose for group photos in uniform, standing in front of the company logo.

It’s hard to overstate how wild that is. Imagine folks from CrowdStrike or Google TAG doing press shoots in fatigues, proudly identifying themselves as part of the U.S. military’s order of battle. It’s like if Palo Alto Networks or Cisco had an official unit patch (Wait… actually kind of a sick idea. Note to self: pitch this for the next round of Margin swag).

A final point that bears emphasizing: China’s cyber militia units don’t just coordinate with the PLA. They report to it. These formations are part of the formal command architecture, answering upward through the PAFD to the relevant Theater Command. That’s a major departure from the U.S. model. American companies may augment government cyber capabilities, but exist outside of the formal chain of command structure. If you want an (imperfect but illustrative) U.S. comparison, imagine if Microsoft had a cyber unit that didn’t just help CYBERCOM— it was part of CYBERCOM. That’s the level of integration we’re talking about here.

So, What Are We Supposed to Do With This Information?

Alright, that’s the ride. Obviously, this piece took a very different tone from the original report. And yeah, some of it was oversimplified. But the goal wasn’t to dumb things down. Rather, it was to make China’s cyber militia mobilization structure legible for folks who don’t spend their free time decoding Chinese military org charts. Because the bigger picture is worth understanding, and let’s be honest, most people don’t have time to dig through 50-page PDFs just to get to the part where cybersecurity analysts start posing in uniform.

To be clear, the end goal of this research isn’t hyping “China bad” narratives or fear-mongering for the sake of it. It’s about understanding how a different system of governance creates a different kind of operational logic. Moreover, it’s about tracing how political structures shape technical realities and why that matters for anyone who cares about national security, cyber operations, or the bureaucratic machinery that underpins policymaking.

Nevertheless, the growing role of Chinese civilian actors (particularly private cybersecurity companies) in provisioning cyber militia units is a development that should not be overlooked by policymakers. For one thing, if you’re trying to estimate China’s wartime cyber capacity, and you’re not factoring in these militia units, then you’re undercounting. Mass matters. And when that mass is made up of work-unit-sourced cyber detachments doing things like rear-echelon network ops and comms support, that means PLA active-duty teams get to spend their time doing the more scary stuff.

At a more structural level, the blurred line between civilian firms and military force contributors warrants a reassessment of how we treat companies like Qihoo 360 and Antiy. These entities are not merely private-sector actors; they are active participants in China’s military mobilization system. They should be treated accordingly, whether through sanctions, export controls, or other tools typically applied to defense-linked entities like NORINCO and CETC.

There’s more I could’ve covered (so, so much more), but I’ll leave it here for now. If this scratched an itch, the full report goes deeper, and the sources I linked throughout are very solid jumping-off points. More importantly, I hope it helps open up better, more interesting conversations between the cybersecurity and China-watching communities that go beyond the latest APT activity and into how these systems actually work. I think we all benefit from that kind of cross-pollination.

(Also, keep an eye out for Margin camo patches. Probably. Maybe. At this point I’m just trying to wish-cast them into existence… but hey, they’re a vibe).