Russia’s largest hacking conference, Positive Hack Days, recently took place in Moscow from Friday, May 19 to Saturday, May 20. The event was held at Gorky Park, a large park and cultural complex in Moscow, and split into an area freely open to the public and a village area that required a purchased ticket.

Many Russian companies are using open-source technology wherever possible. Russia still struggles to replace foreign-made hardware. Transparency has fallen in Russia’s cyber sector since February 2022, including because many companies are “shadow” installing foreign tech and not reporting it. Demand for cybersecurity services in Russia is growing across the board, except for insurance. These and many other points were made during the conference—an important, annual window into some of the companies, individuals, and conversations driving Russia’s cybersecurity scene.

The conference is organized by Positive Technologies, a major (and quickly growing) Russian cybersecurity firm that conducts cybersecurity research and provides services to public- and private-sector clients. Positive Technologies was sanctioned by the US government in April 2021 for providing cyber support to the Russian intelligence community. Per the US government’s sanctions announcement, the Russian security services also use Positive Technologies events to recruit hackers to work for the government. Positive Technologies is an important part of Russia’s national cyber threat response program (GosSOPKA) as well. (GosSOPKA has been described by Moscow as a cyber “shield” to defend Russia but in practice consists mainly of cyber threat intelligence and incident response functions, alongside information-exchange centers embedded at “critical information infrastructure” facilities.)

At last year’s Positive Hack Days, cybersecurity companies, researchers, and state officials emphasized themes such as the importance of Russia’s domestic technology sector, the impact of Western sanctions, and the Russian government’s push for domestic tech development. Some individuals expressed concerns about growing technological isolation in Russia, too. The government attendees repeatedly spread nationalistic rhetoric.

Margin Research has previously conducted analyses on Positive Technologies as part of Margin’s work on DARPA’s SocialCyber project—or Hybrid AI to Protect Integrity of Open Source Code. I also conducted a detailed analysis of Positive Hack Days in 2022 and wrote up some of the significant takeaways for the Brookings Institution.

This post analyzes some highlights from Positive Hack Days 2023 and how they fit within Western sanctions, Russia’s technological isolation, and the Russian push to use systems like Astra Linux.

Main Organizations at Positive Hack Days

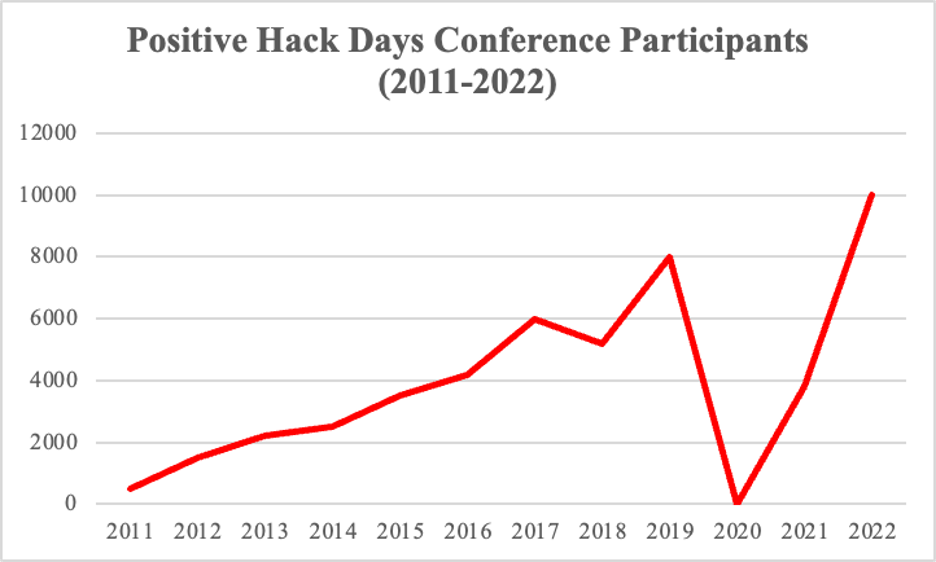

Positive Hack Days has rapidly grown since its inception in 2011. While attendance figures are not yet available for 2023, there were a record 10,000 attendees in 2022. Growth from 2011 to 2022 has otherwise been relatively steady, except for 2020, when the conference was canceled due to COVID-19, and 2021, when attendance numbers were still recovering.

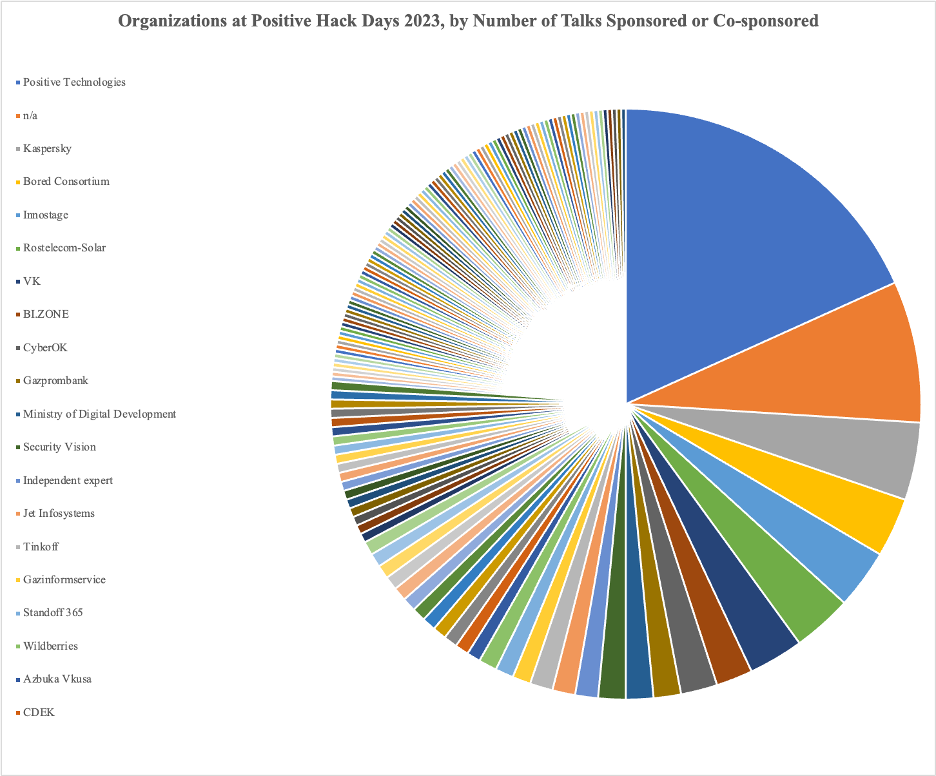

The 2023 conference featured talks, panels, discussions, and the conference’s signature “Standoff” hacking competition, where teams compete to break into and defend targets. Across those numerous talks and panels, 143 different organizations were represented. They included conference organizer Positive Technologies; important Russian cybersecurity companies such as Kaspersky, BI.ZONE, and Rostelecom-Solar; Russian tech giant VK (formerly VKontakte); government agencies like the Ministry of Digital Development; and independent security researchers and analysts.

Broken down by the number of talks sponsored or co-sponsored—when a talk or panel had at least one member of the organization participating—the most represented organization was Positive Technologies. This was followed by entities marked “n/a” for their affiliation, often including independent security researchers; cybersecurity company Kaspersky; the Bored Consortium cryptocurrency community at ITMO University, a Russian national research university; cybersecurity company Innostage; cybersecurity company Rostelecom-Solar, which was purchased by state-owned telecom Rostelecom in 2018 (when it was “Solar Security”); and tech conglomerate VK (formerly VKontakte). VK is the parent company for the social network VKontakte, dubbed “Russia’s Facebook” because of its virtually identical design, as well as the Mail.ru email service, the VK Pay digital payments system, and many other tech products and services.

There were just three talks with representatives from Yandex Cloud, the cloud arm of Russian internet giant Yandex. Margin Research recently conducted an analysis of Yandex (including Yandex Cloud) using its SocialCyber capabilities. That analysis suggested that the high number of both Yandex employees in Russia and open-source code contributors in Russian time zones would complicate Yandex’s reported plans to split its business within Russia from its business outside of Russia.

Within those organizations, many US- or EU-sanctioned individuals also attended. In addition to Positive Technologies employees, cybersecurity practitioner Alisa Shevchenko attended, representing the company Zero Day Engineering LLC. Shevchenko’s old company, Zorsecurity, was sanctioned by the US government in December 2016 for providing “technical research and development” to the GRU and its 2016 election interference. It appears she has created a new company—and perhaps aptly named. (Her presentation this year covered modern attacks on Google Chrome.) Other sanctioned organizations like Gazprombank—privately owned but state-linked—had representatives in Moscow for the event as well.

Russian Government Presence at Positive Hack Days

At most cybersecurity conferences around the world, the government of the host country has representatives in attendance. Positive Hack Days is no different.

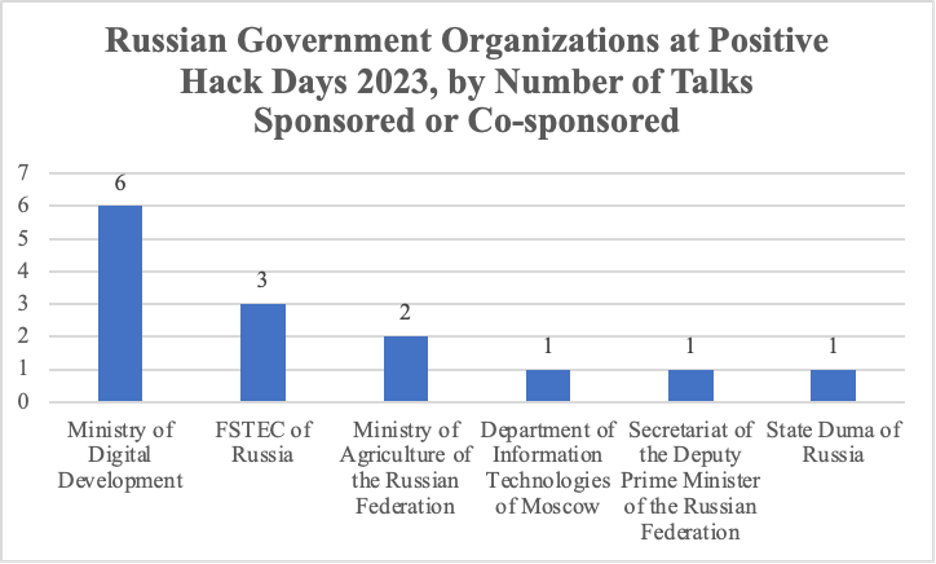

This year, notable Russian government attendees included the Minister (Maxut Shadaev) and Deputy Minister (Aleksandr Shoytov) of the Ministry of Digital Development, the head of its Information Security Department (Vladimir Bengin), and representative Andrey Svintsov from the State Duma (lower house of Russian parliament). Attending as well, among others, were Sergey Scherbakov from the Deputy Prime Minister’s office and Vitaly Lyutikov, the deputy director of FSTEC, Russia’s Federal Service for Technical Export and Control. FSTEC sits under the Russian Defense Ministry and is responsible for the military’s “information security” and for managing import and export licenses on dual-use items. As part of that activity, FSTEC also conducts source code reviews of technology products and manages a Russian government vulnerability database.

These attendees signal that the Russian government has continued interest in strengthening Russia’s cyber community and in communicating its policies to promote the development and use of domestic, Russian tech.

Maria Zakharova, the notorious Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson in attendance in 2022—who BuzzFeed News dubbed Russia’s “troll in chief” for her lies and what-about-ism—did not attend this year. But Maksut Shadayev, the Minister of Digital Development, has attended multiple times before. His panel discussion this year covered how 2023 was a “watershed” moment for Russia’s technology sector due to sanctions on Russia, foreign company exits, and the challenges of growing tech isolation. Other government discussions covered such topics as every question you might want to pose to a regulator but “didn’t dare” ask. It is notable that both the Minister of Digital Development and a representative from the Deputy Prime Minister’s not only attended but spoke at Positive Hack Days.

As in previous years, of course, some speakers were in explicit agreement with the government officials on their panels. There was discussion of what was called the “cyber war” facing Russia and praise for state policies to increase the adoption of Russian software. But many individuals in Russia are in increasingly difficult positions, and there could have been individuals on those panels who disagreed in different ways but did not express as much. This could include private-sector cyber executives unhappy with Russian government software replacement policies and independent cybersecurity researchers who wish to maintain robust connections with Western collaborators. Further, of course, mere attendance of the conference does not necessarily denote agreement with government speakers’ comments.

Takeaways and Looking Ahead

At the conference talks, a number of comments were made, including:

- Market transparency in the Russian cyber sector has fallen post-February 2022 (after—which participants did not say—the Russian government launched a full-scale, illegal war on Ukraine and was hit with Western sanctions), including because many companies are “shadow” installing foreign tech products and not reporting it.

- Demand for cybersecurity services is increasing in most sectors, except insurance.

- There are still many barriers within Russia’s cyber sector to effective cooperation and threat information-sharing, as well as in developing community platforms for practitioners to communicate with one another.

- Ransomware groups targeting the Russian private sector have, among other things, exploited vulnerabilities in Linux.

- Many companies are using open-source technology where possible.

- Russia still struggles to replace foreign-made hardware, including because Russia does not have the requisite domestic microelectronics manufacturing capability.

- Technological independence does not mean technological isolation, and Russia should explore working more with Asian countries, such as India, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) countries (which includes China) on tech development.

There was also the four-day-long “Standoff” hacking competition. It focused this year on teams breaking into and defending a fictional banking system, city housing and utility system, and atomic energy system. Participants attacking these systems identified vulnerabilities such as remote code execution and triggered events such as leaks of confidential information and ransomware infections. In other hacking exercises separate from the Standoff, hackers in attendance practiced defending networks, looking for vulnerabilities, and hacking into ATMs, mobile banks, and cash registers. Several hackers also participated, some successfully, in a contest to break into smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain network. Some stole money; others modified the smart contract itself.

Positive Hack Days’ to-be-released 2023 attendance figures will indicate whether the event has grown following Western sanctions and a significant “brain drain” of tech professionals. (According to December 2022 estimates from Russia’s Ministry of Digital Development, about 10% of the country’s entire information technology sector left the country after February 2022.) For now, though, the government officials’ attendance indicates that at least some senior Russian figures want to build out Russia’s cyber sector and push for more technological independence. And while mere attendance does not imply endorsement of any views stated during the talks, many companies expressed they were happy to be supporting the Russian government and its domestic tech policies.