On October 28, I had the opportunity to present at the 2022 JailBreak Security Summit, focused on Margin Research’s SocialCyber work on Russian offensive cyber. The presentation was titled “Russia’s Open-Source Code and Private-Sector Cybersecurity Ecosystem.” A video to the conference talk can be found here. It covered Russia’s open-source code ecosystem, key Russian private-sector cybersecurity actors, and the future of Russia’s hacker ecosystem. This blog post summarizes some of the main points from the talk.

SocialCyber is the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)’s project on Hybrid AI to Protect Integrity of Open Source Code. Driven by the Defense Department’s use of open-source code, the project seeks to understand the key players in the open-source code ecosystem, and how the community and the code can come under threat. SocialCyber approaches these risks broadly, including assessment of the ways a malicious actor could target developer communities with information operations, submit flawed code or designs, interfere with open-source software vulnerability mitigations, file misleading bug reports, disrupt technical discussions, and socially capture functional authority on open-source software projects.

In support of this work, Margin Research has focused on the Linux Kernel. This entails understanding the critical contributors to the Linux Kernel, combining Linux-related data from GitHub with data from Twitter and other sources, and developing ways to annotate the data. For example, a finding from Margin Research’s work is that individuals affiliated with Huawei were the top contributors to the Linux Kernel in 2021, even surpassing contributions by individuals working at Intel. Once the data is compiled on key contributors to the Linux Kernel, Margin Research enlists subject matter experts to conduct further analysis on companies, research institutions, and individuals.

Russia and the Linux Kernel

One of Russia’s top contributors to the Linux Kernel works at Positive Technologies, a major Russian cybersecurity company sanctioned by the US in 2021 for supporting the Russian government’s cyber activities. This matters for several reasons. In and of itself, this finding is valuable for understanding who in Russia drives changes to the widely used Linux operating system. It is also valuable because the individual’s contributions to the Linux Kernel appear benign. The Russian government has pushed to replace Western technology with domestic, Russian-made technology—including to replace Microsoft Windows with the operating system Astra Linux. Hence, there are plenty of reasons for the Russian government to want the Linux operating system to be more secure and for a major Russian government contractor like Positive Technologies to genuinely invest in better protecting Linux.

Simultaneously, this raises a host of security questions with unclear answers. Reportedly, the US government has found that Positive Technologies develops and supplies exploits to the Russian government. Granted, it is a large company and advertises many defensive security services; Positive Technologies, like many organizations, could have many different sub-teams looking at different problems. For example, it could have a split between its more offensive and its more defensive personnel. Simultaneously, however, employees who research vulnerabilities may be required to pass them along internally before they are disclosed, or employees may be instructed to avoid disclosure altogether.

Russian Cybersecurity Firms and the Russian State

Private-sector cybersecurity companies in Russia likewise play a crucial role in this cyber ecosystem. Not all Russian cybersecurity companies directly support the government. Many do support the government, though, and might aid with everything from building talent to developing capabilities to supporting state operations. (This is one of multiple differences between the Russian and Chinese domestic cybersecurity ecosystems, as many Chinese cyber firms are compelled to support Beijing.)

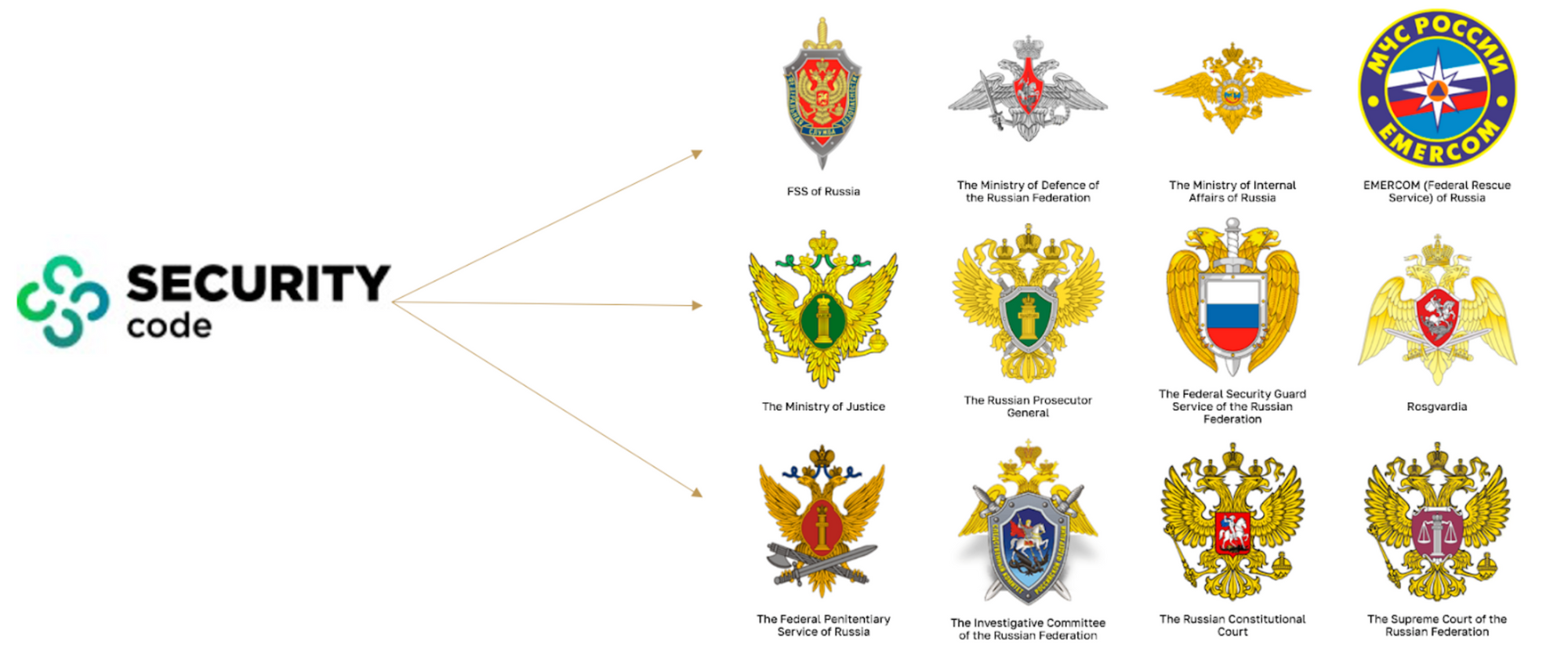

For example, Security Code is a major Russian cybersecurity company that offers cybersecurity solutions and services for government agencies and enterprises to protect themselves. It includes among its clients the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Internal Affairs (which runs the national police), the Russian Prosecutor General, the National Guard (Rosgvardia), the Ministry of Finance, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, among others. It also provides services to major state-owned conglomerates like Rosneft, the energy company, and Sberbank, the state-owned bank and financial services firm.

It is plausible based on publicly available information that much of what Security Code provides for the Russian government is defensive. Nonetheless, it is also possible some firms that appear defensive in their public-facing content provide covert support for the government’s offensive actions, akin to the information technology firm Neobit that covertly supports cyber operations run by the FSB, Russia’s military intelligence agency (GRU), and Russia’s foreign intelligence service (SVR).

Some firms do supply offensive cyber support to the Russian government. Positive Technologies was founded in 2002 with just a few employees in a Moscow office, and since, the cybersecurity company has grown to well over 1,000 employees in several countries around the world (from the United Kingdom to India to South Korea). The US Treasury Department said in April 2021, when it sanctioned the company, that Positive Technologies supports the FSB, among other Russian government clients. Other reporting states that Positive Technologies also works on discovering vulnerabilities in hardware and software, developing exploits for those vulnerabilities, and then passing those exploits to the Russian government.

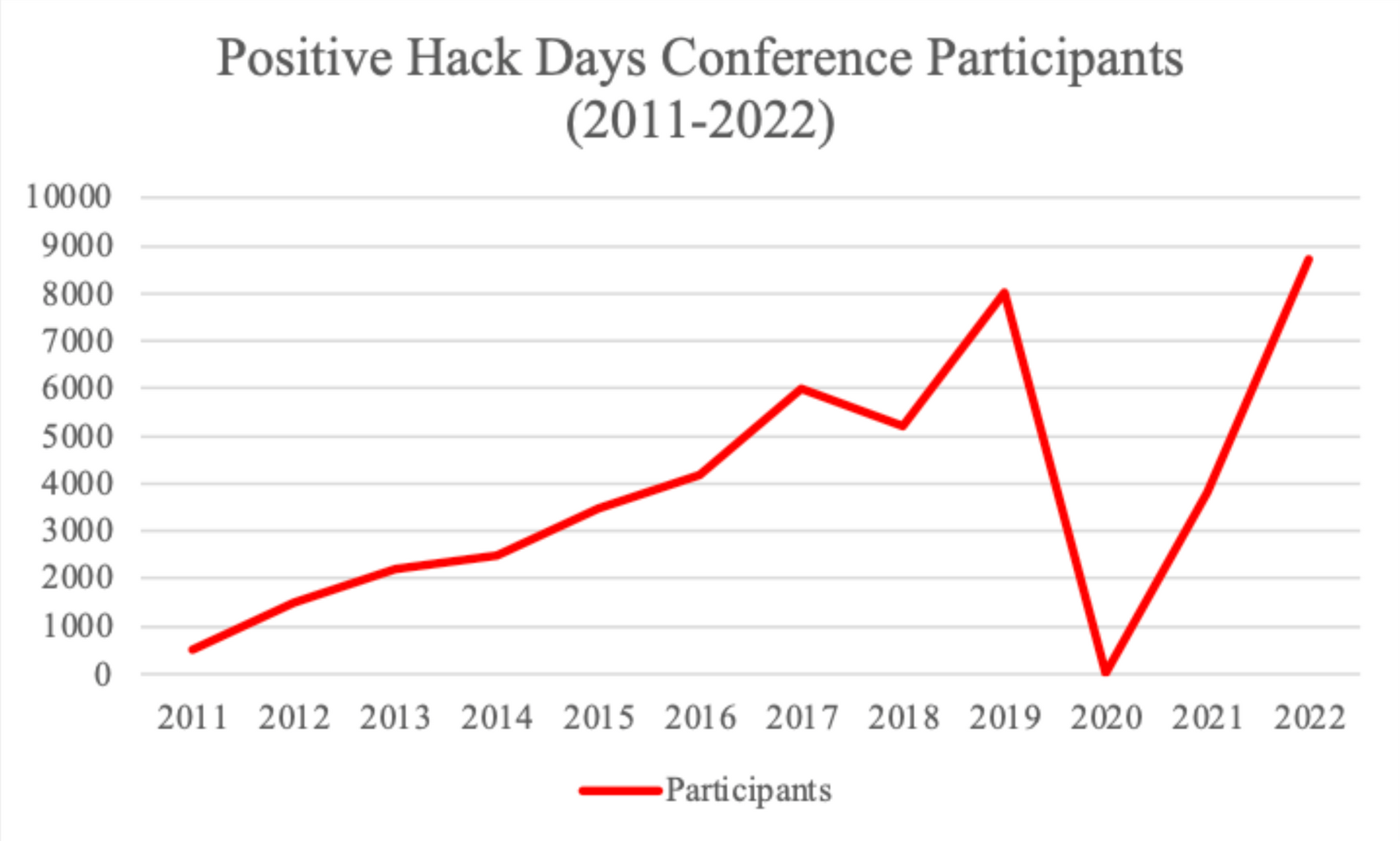

Treasury also stated that Positive Technologies “hosts large-scale conventions that are used as recruiting events for the FSB and GRU.” Its signature security conference-meets-capture the flag competition, Positive Hack Days, appears to be one such venue. The conference began in 2011 with around 500 participants. Since then, it has grown into a large event for the Russian hacker community: the 2022 Positive Hack Days featured dozens of speakers, had dozens of partners across the Russian cyber ecosystem, and saw nearly 9,000 people in attendance.

Previous reporting has identified Russian intelligence personnel attending the event, ostensibly to recruit talented hackers to work for the state.

The capture the flag competition entitled Moscow CTF is a similarly interesting case study in the Russian private sector facilitating talent sourcing for the Russian government. Russia’s Association of Chief Information Security Officers launched the competition in 2010. That same year, the FSB started using the event to recruit hackers. In 2015, the Ministry of Defense took note and itself began sponsoring the event and using it to recruit hackers. In 2021, its sponsors ranged from Voentelekom, a Russian telecommunications equipment supplier, to Infotecs, on the US Entity List for enabling “the activities of malicious Russian cyber actors.”

In some ways, this is an issue familiar to other countries: Moscow has to deal with cyber talent sourcing challenges, and it leverages capture the flag competitions, hacker conferences, and other events to do so. At the same time, however, the issue is unique in the Russian context given the declining Russian economy, the longstanding “brain drain” of tech talent from Russia (as people move abroad), and the state’s ability to coerce developers through force. Russian authorities can pressure developers and even cybercriminals and other actors to bend the knee if they so choose.

This is just a sample of the snapshot Margin Research is putting together on the Russian open-source code and private-sector cybersecurity ecosystem. Looking forward, these issues will become even more important for understanding the cybersecurity threat landscape, foreign hacker communities, and how open-source code intersects with offensive cyber capability development, foreign cyber talent recruitment, and other issues.

The Kremlin is clearly intent on using all means available to project power, and the question of how it sources cyber talent, develops capabilities, and even launches cyber operations will depend on its access to a tangled web of cyber actors at home.