So, you want to start reverse engineering MikroTik routers. Where do you start? As opposed to many routers which act more as a collection of independent binaries for each service, MikroTik devices implement a system of interconnected binaries which perform tasks for one another. Unfortunately, there is limited publicly available information about how this system-wide implementation works, and the good, technical information available is now a few years old. In that time, MikroTik released a number of minor version updates and one major revision software upgrade, making some of the technical details obsolete.

Consequently, we are left generally in the dark as to how MikroTik works, and digging into its dense, hand-rolled C++ binaries filled with custom library calls is a daunting task.

This blog post, which overviews our presentation at REcon 2022, outlines key knowledge and introduces tools that we created during our research over the past handful of months.

The goal of that talk, and this post, is to refresh the publicly available MikroTik knowledge and provide a crash course on MikroTik internals that will bring you from potentially zero experience to a point where you are familiar and comfortable with key MikroTik concepts and abstractions.

This knowledge will jump-start your research, tool development, or whatever MikroTik-related tinkering in which you are interested. Let's get started!

Overview

We approach our overarching goal in four ways: first, we dive into MikroTik's RouterOS operating system, understanding how it loads firmware and boots processes. Specifically, we focus on how firmware packages are cryptographically signed, and how we can bypass signing to obtain a developer shell in a MikroTik RouterOS virtual machine. Next, we focus on a key concept central to MikroTik: its proprietary messaging protocol used for IPC. Third, we dive into how we can authenticate to different services, specifically reviewing a proprietary, hand-rolled cryptographic protocol used for multiple publicly exposed services. Finally, we introduce a novel post-authentication jailbreak for MikroTik devices running v6 firmware (current long-term release branch) that pops a shell on any virtual or physical device.

Diving Deep into RouterOS Internals

NPK Files and Backdoors

Unlike some IoT devices which frustratingly require intercepting software downloads or extracting firmware directly from hardware, MikroTik hosts its proprietary firmware on its software downloads page. This conveniently allows us to investigate firmware components and understand how RouterOS, MikroTik’s customized operating system, is organized. Opening up the file system, we see the following components:

/flash/rw/{disk, logs, tmp, store...}- writable region/lib- core libraries/nova/bin- system binaries/nova/lib- system libraries/nova/etc- system configuration/pckg/{name}/nova/{bin, lib, etc}- package data

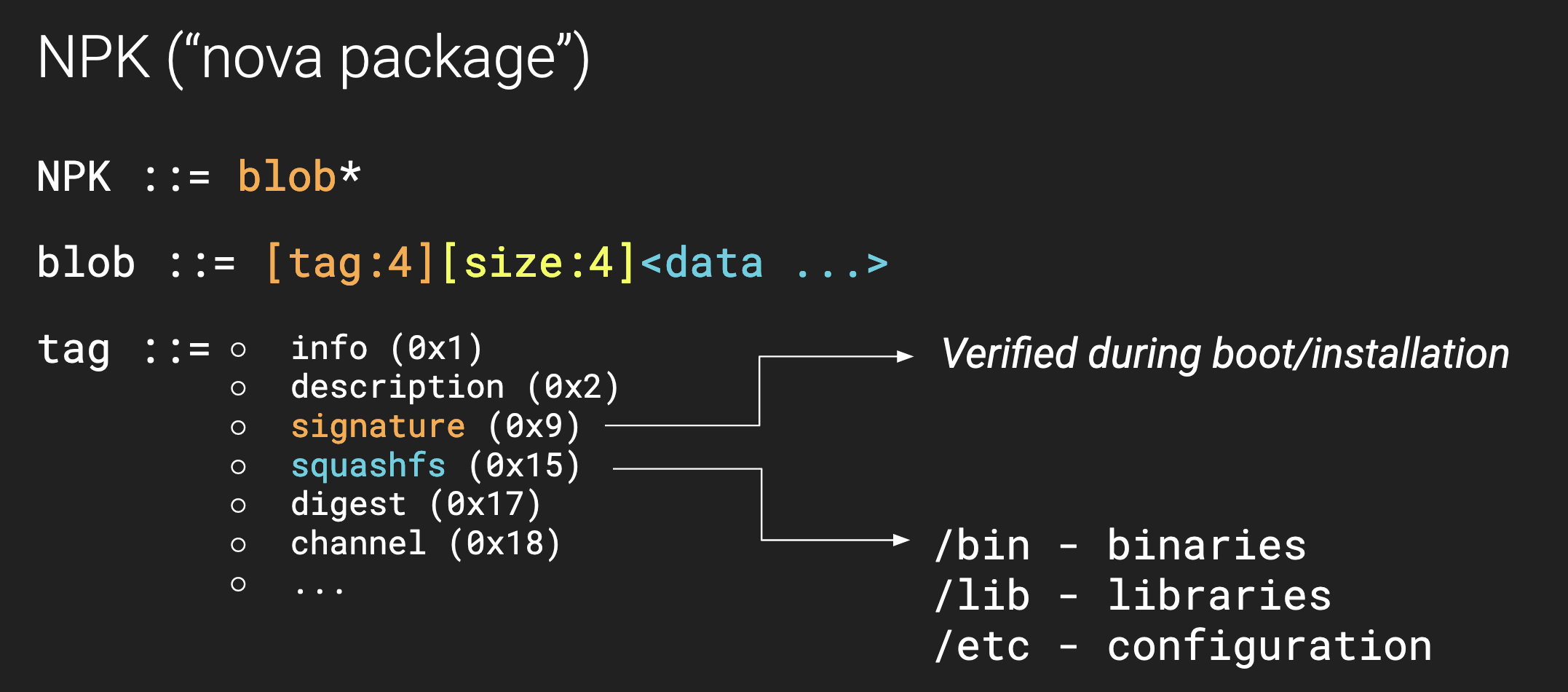

RouterOS software is distributed in .npk files (which we think stands for “nova package”). In recent versions of RouterOS, each NPK file contains a squashfs with the package data along with a cryptographic signature that RouterOS verifies during installation and every reboot.

While RouterOS is locked down - meaning we cannot easily get a developer shell - there is a known backdoor that has existed for a long time. Specifically, if we login as the devel user with the admin password and have the option package installed, RouterOS launches /pckg/option/bin/bash instead of the default restricted shell.

That is exactly what we want for security research! However, there are two problems:

- The

optionpackage does not exist outside of MikroTik offices (of course...) - Packages are signed, which means we cannot easily construct our own

optionpackage

In some previous versions of RouterOS it was possible to leverage known CVEs to “install” the option package post-boot and enable this developer backdoor. See Jacob Baines’s Cleaner Wrasse program for an example of an automated tool that accomplishes this.

However, since version 6.44 (2019), this tool no longer works and we need a different strategy…

Bypassing Signature Validation

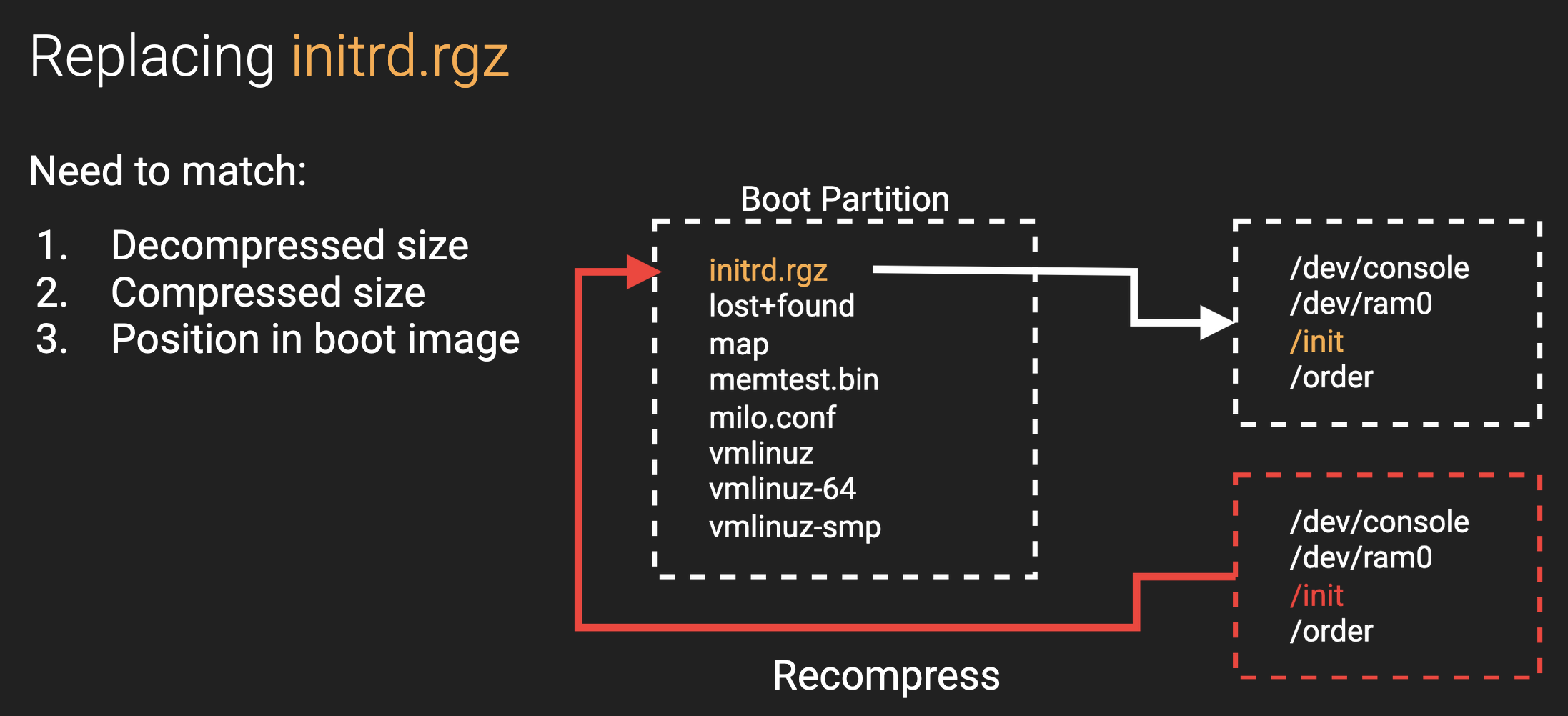

Since we are hackers with unfettered access to the RouterOS firmware, let's go straight to the source and figure out how RouterOS actually validates packages. After a bit of poking around, we discover that package validation occurs in the init binary, a part of the compressed initrd.rgz file located in the disk image's boot sector.

Luckily for us, the init binary invokes a single function to validate each package. We can find this function by looking for a reference to the %s/flash/var/pdb/%s/disabled string. In pseudo-code, the function works as follows:

int check_signature(...){

// magic

snprintf(buf, 0x80, "%s/flash/var/pdb/%s/disabled");

return is_valid;

}All we need to do to bypass signature validation is find this function and patch it to return 1 every time. However, we run into a problem when we try to recompress this and patch our original initrd.rgz…

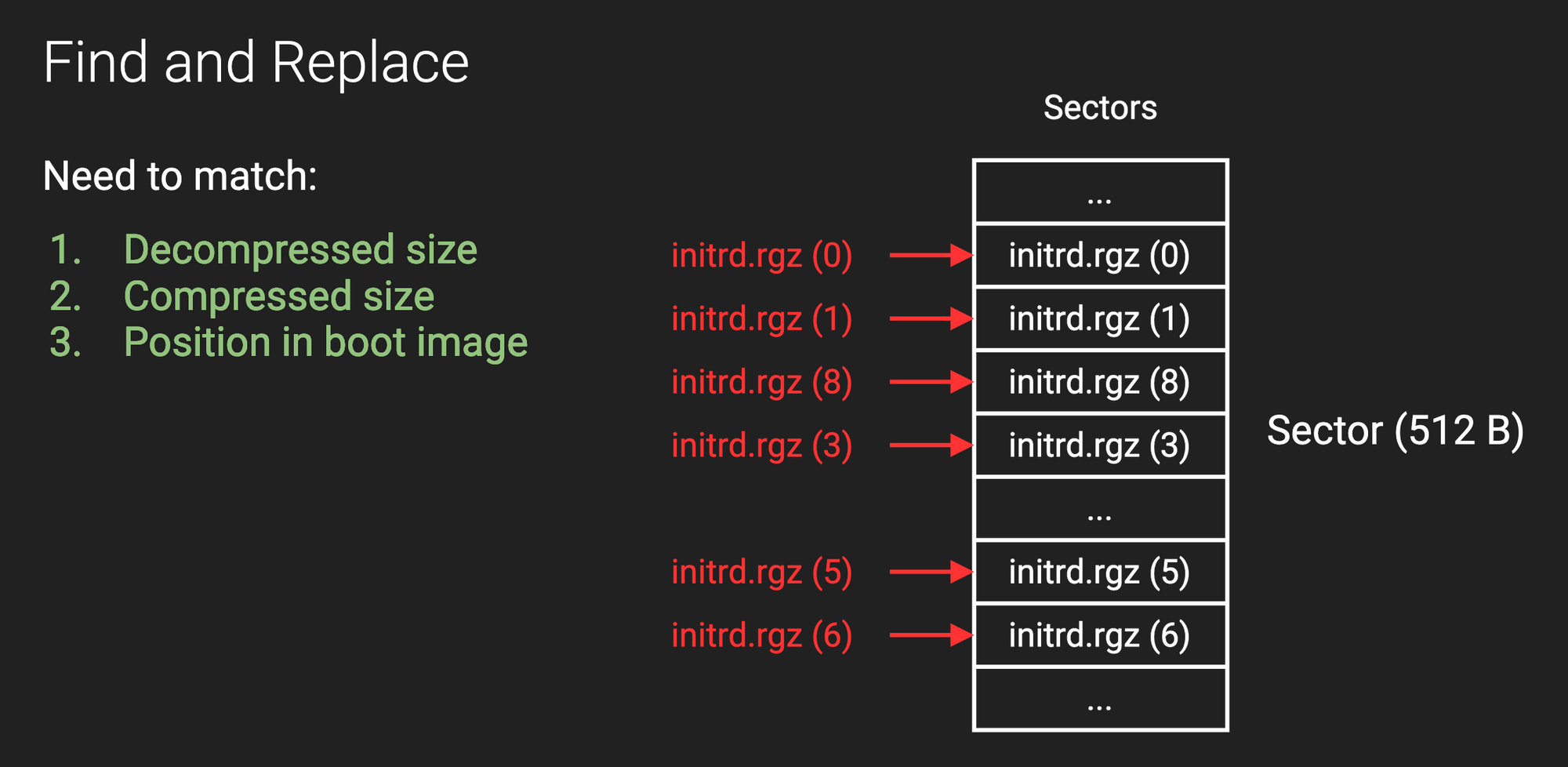

It turns out that the kernel is very finicky about what initrd.rgz looks like. Specifically, we need to make sure that we match the expected size (both compressed and decompressed) and also the exact position in the disk image. If we do not match these properties then the kernel fails to decompress initrd.rgz and the router fails to boot.

The "Entropy Trick"

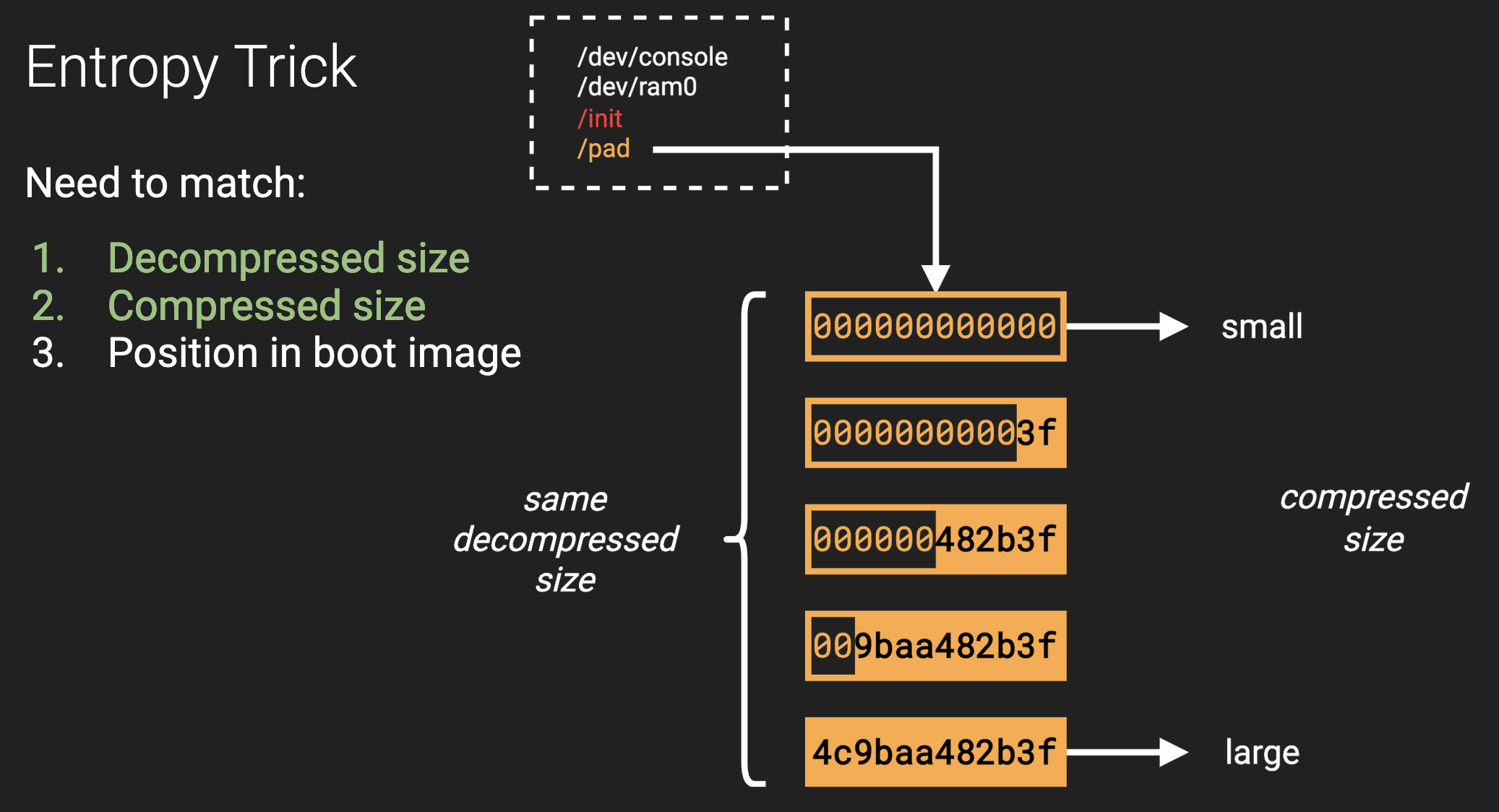

To solve the first two constraints, we make use of an “entropy trick.” Specifically, we create a dummy file, pad, inside our initrd directory and adjust its size to match the decompressed size of the original initrd directory. Then, by adjusting the amount of entropy in the file, we control the compressed size of initrd.rgz:

For example, if pad contains all zeros (low entropy), its compressed size is small. On the other hand, if pad contains all random bytes (high entropy), its compressed size is large. As long as our target size falls between these two extremes, we can perform a binary search on the ratio of zeros to random bytes in order to exactly match the original compressed size.

Ctrl+H

Unfortunately, if we now mount the filesystem in the boot image and copy over our modified initrd.rgz file, the kernel still won’t boot. This is because the kernel expects that initrd.rgz resides at a very specific location in the boot image. When we mount the filesystem and copy the file, it adjusts the position of the actual data. This problem is relatively easy to fix; we can simply do a find-and-replace for every 512 byte sector of the original initrd.rgz and swap it with our modified initrd.rgz. This strategy effectively operates on the raw bytes in the disk image instead of mounting the boot sector as a filesystem.

Unlocking the Backdoor

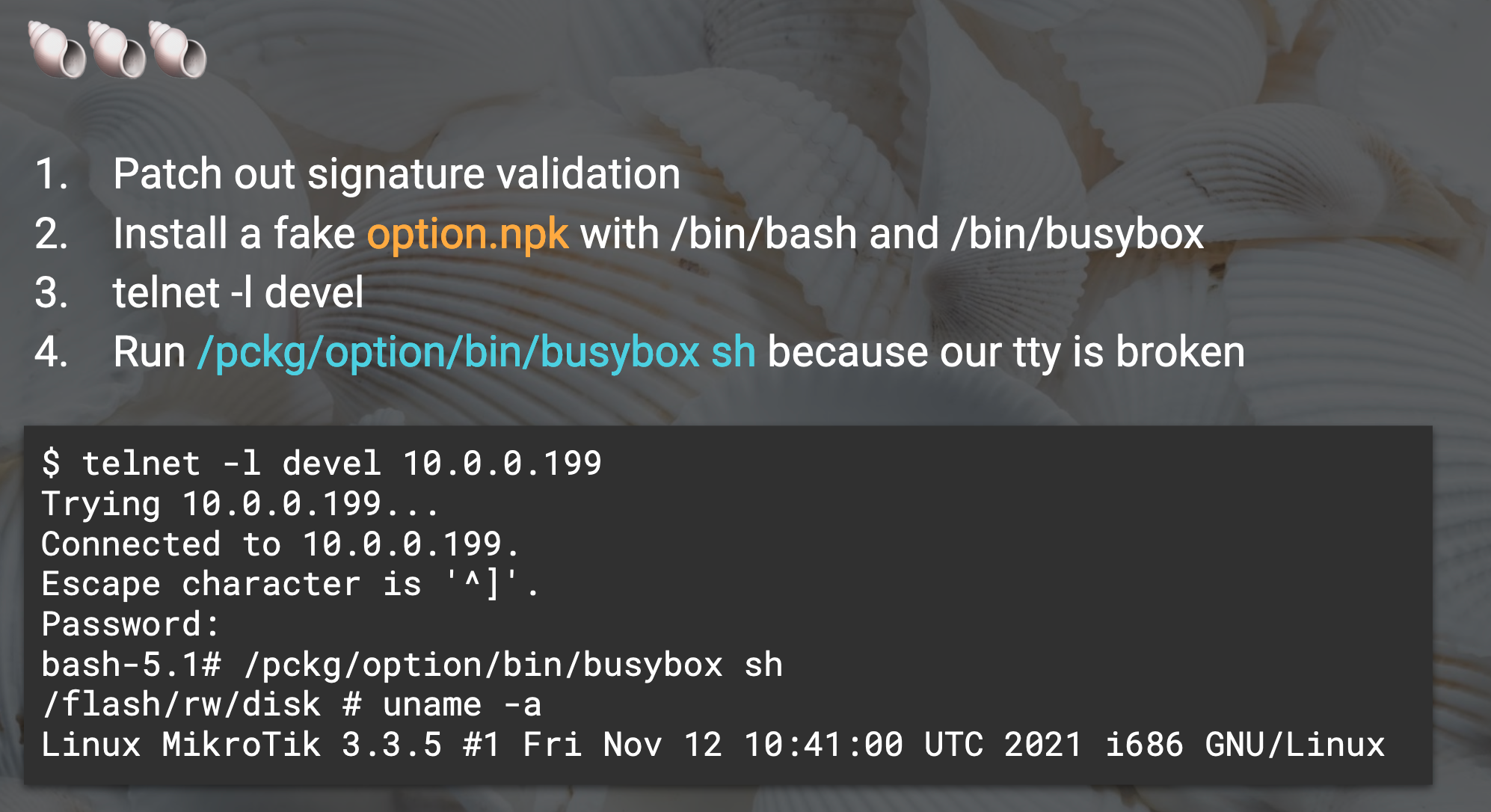

Now that we have successfully patched out signature validation, we are free to install a fake option package (with an invalid signature) and enable our persistent developer backdoor!

It is also helpful to include busybox in the option package for reverse engineering research, since recent versions of RouterOS do not actually ship with any standard /bin tools.

Once we reboot, we can simply telnet -l devel <ip> and provide the admin password to get a familiar bash shell!

RouterOS IPC

Nova Messages

MikroTik designs RouterOS in a very modular fashion. The operating system contains more than 80 processes which communicate with each other through internal messages, and each process is generally responsible for one specific feature. For example, the user binary handles authentication for all other processes.

Upon boot, the init process spawns /nova/bin/loader which is RouterOS’s main control process. loader is responsible for spawning all of the other processes and managing interprocess communication. In some sense, /nova/bin/loader is “the router’s router.”

RouterOS implements the bulk of its IPC in the libumsg.so shared library. This library contains methods for serializing and deserializing messages, constructing abstraction layers to handle requests, and facilitating process-wide communication abstractions. The extensive utilization of this custom framework across RouterOS binaries is one of the things that makes RouterOS a difficult reverse engineering target.

So let’s break it down together.

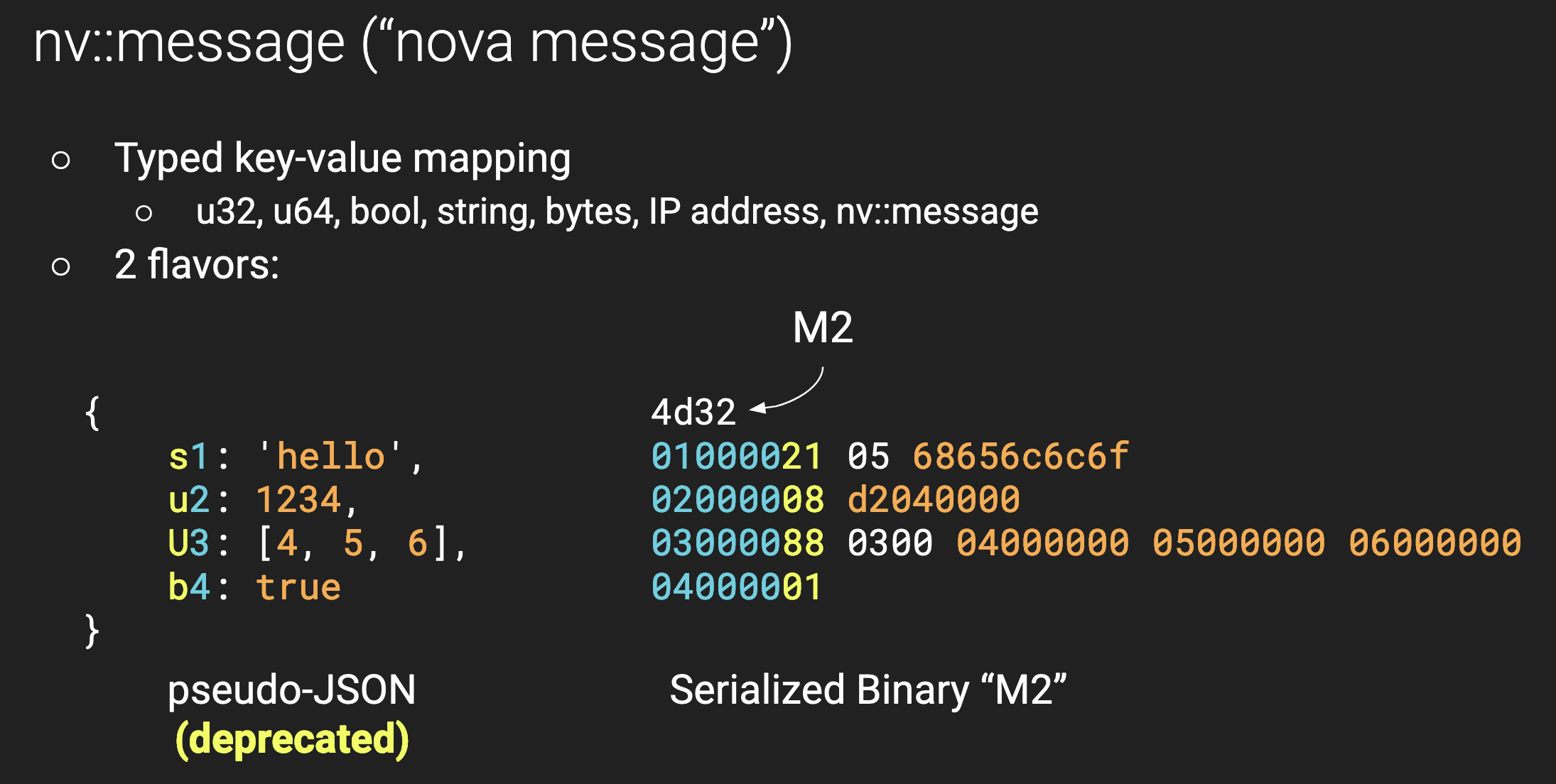

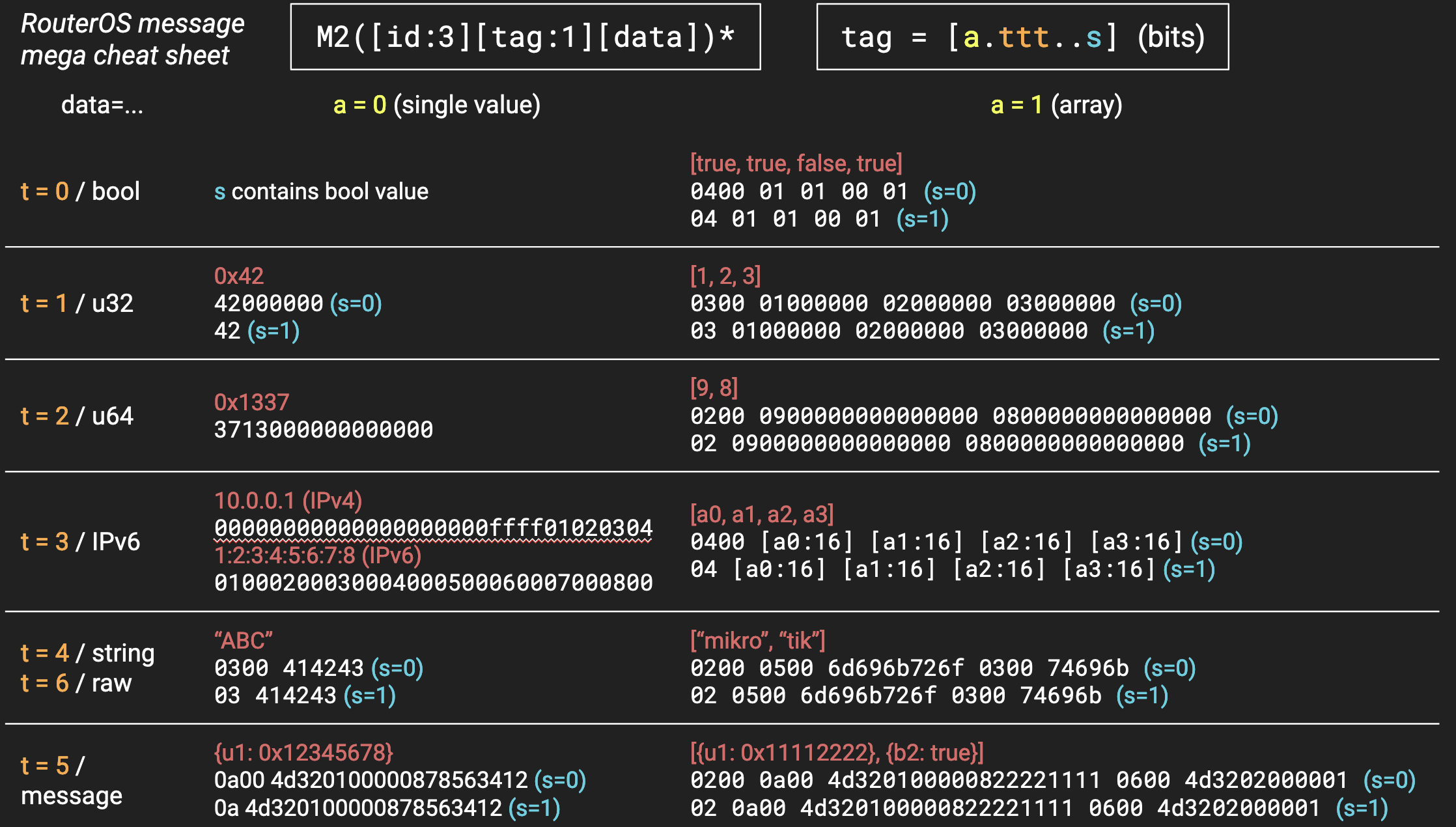

We’ll start with the core player: “Nova Message” (nv::message internally). A nova message is a typed, key-value mapping. It comes in two flavors: a pseudo-JSON variant (now deprecated), and a serialized binary variant. You can recognize the binary messages because they always start with M2 in ascii:

Dissecting a Message

Reverse engineering this message protocol shows that there are six types of data, which can each exist as a single value or as a list. We include the following cheat sheet to describe the serialization format in depth, and you can also find some open-source libraries which implement this protocol.

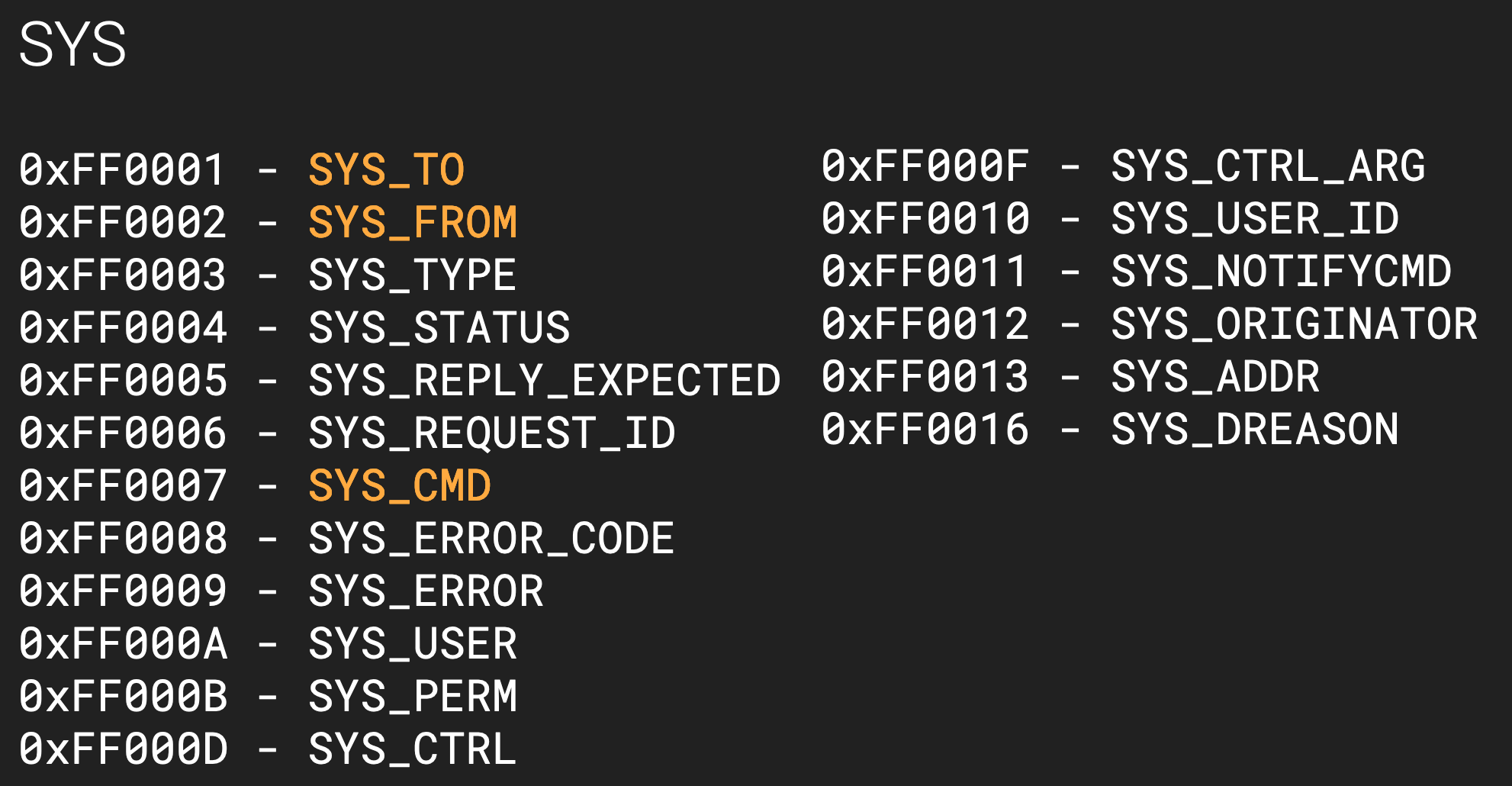

Each nova message key is a 24-bit integer and certain keys have a special meaning inside RouterOS. For example, keys of the form 0xFFxxxx correspond to the SYS namespace and are used during message routing:

Particularly of interest are the keys for SYS_TO (destination binary), SYS_FROM (origin binary), and SYS_CMD (what operation to invoke).

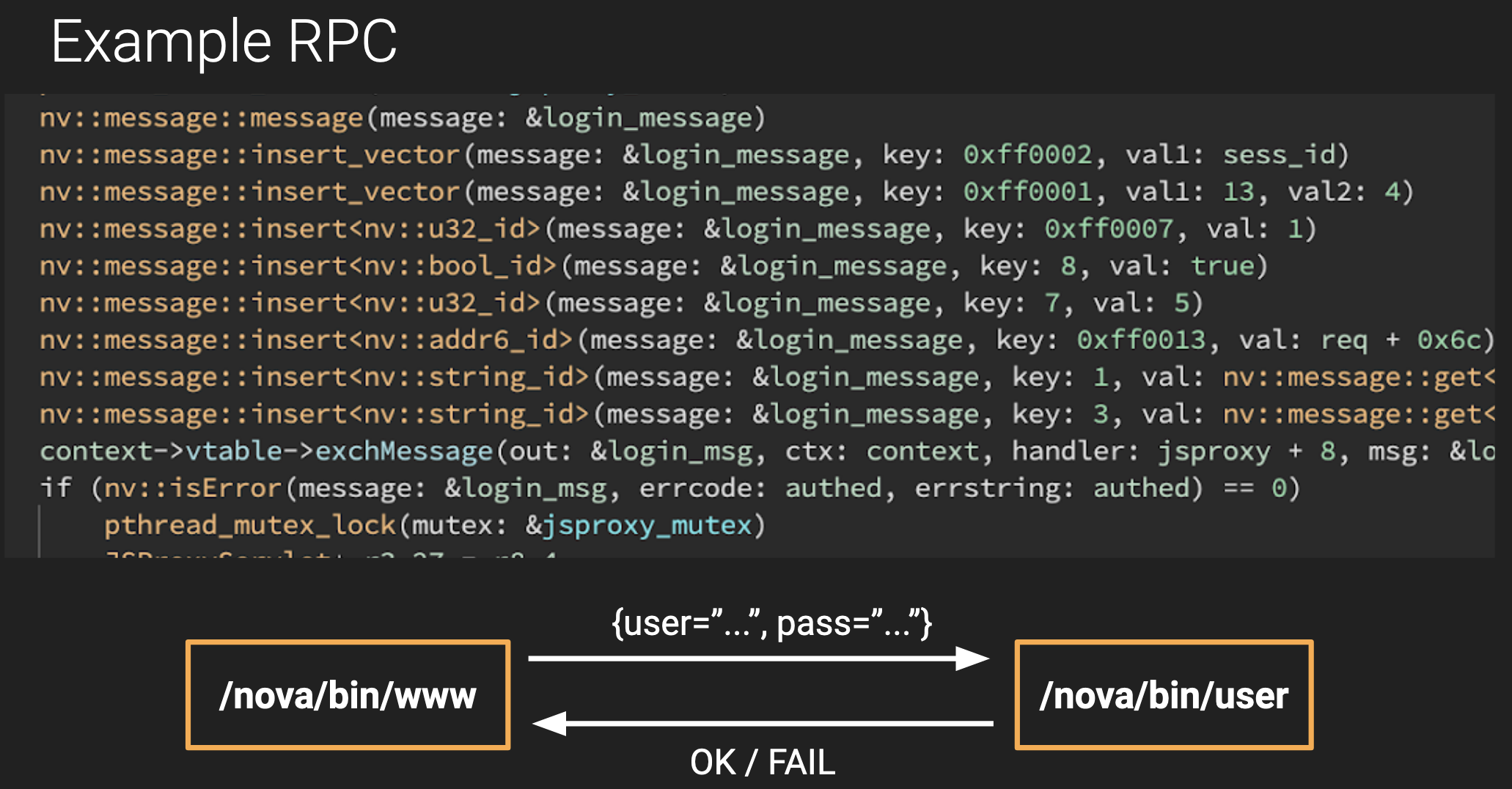

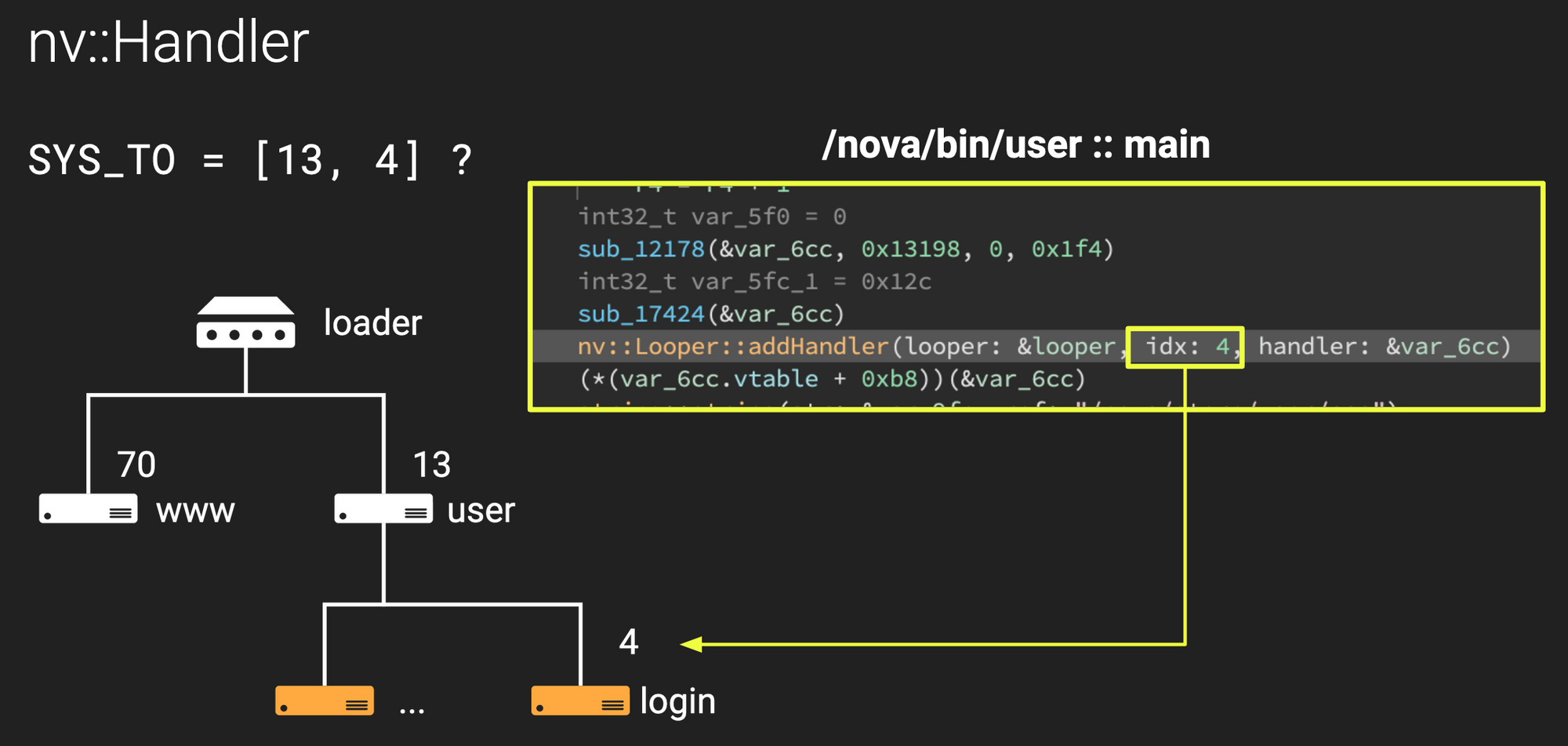

Armed with this information, we can now start to make sense of some RouterOS code. In the following image, we see www sending an authentication request to user. It constructs a new nova message, setting SYS_TO to the address [13, 4] and setting SYS_CMD to 1.

Turning x3 into Pseudo-XML

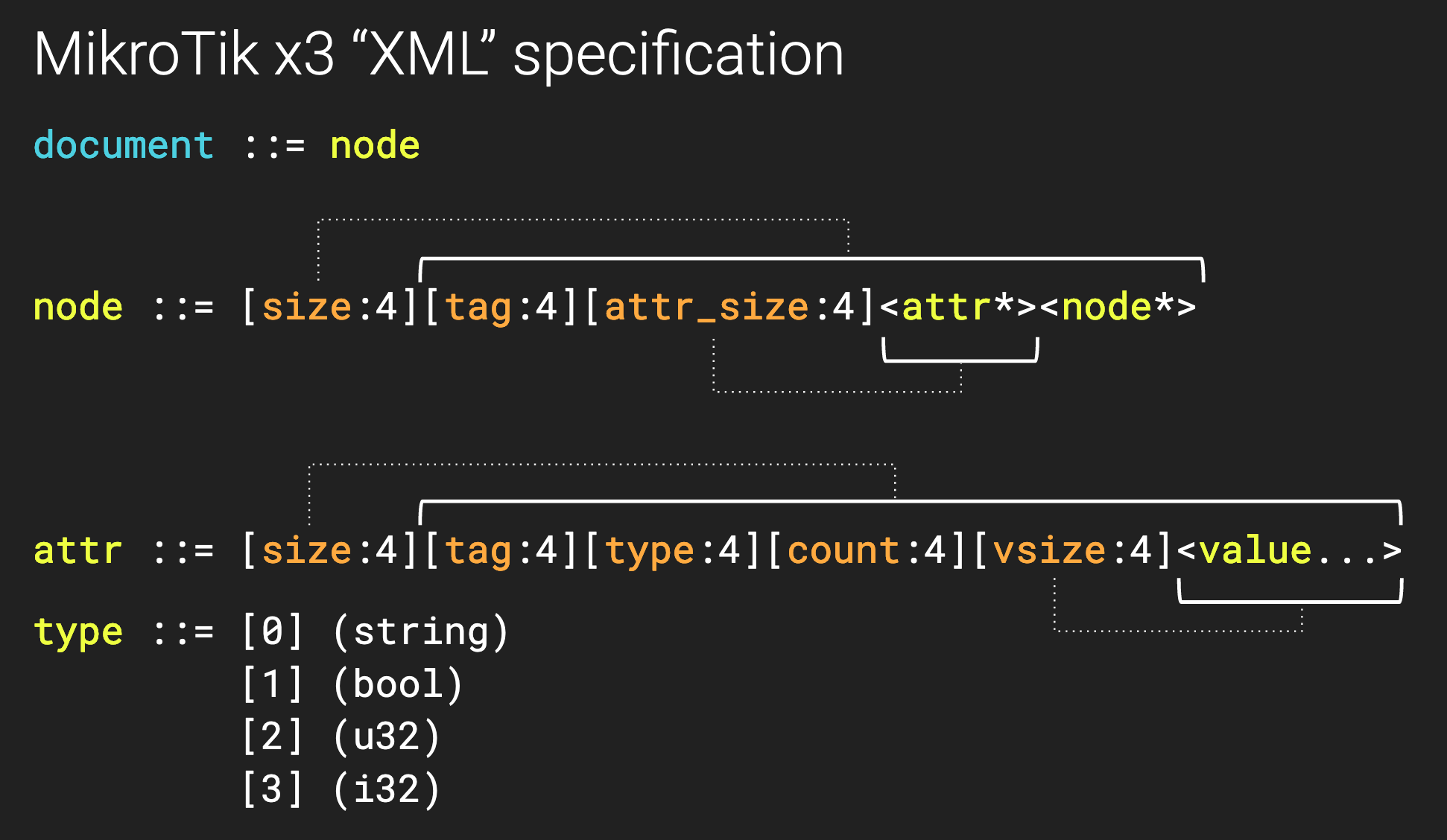

So how do we actually know which process [13, 4] corresponds to? First, remember that /nova/bin/loader is responsible for spawning all the processes. When we look inside loader, we see it reads from a configuration file at /nova/etc/loader/system.x3 using functions in the libuxml++.so library. Unfortunately, this .x3 file is not plain XML but appears to be some serialized format. With a bit of reverse engineering and some coffee, we recover MikroTik’s “pseudo-XML” format specification:

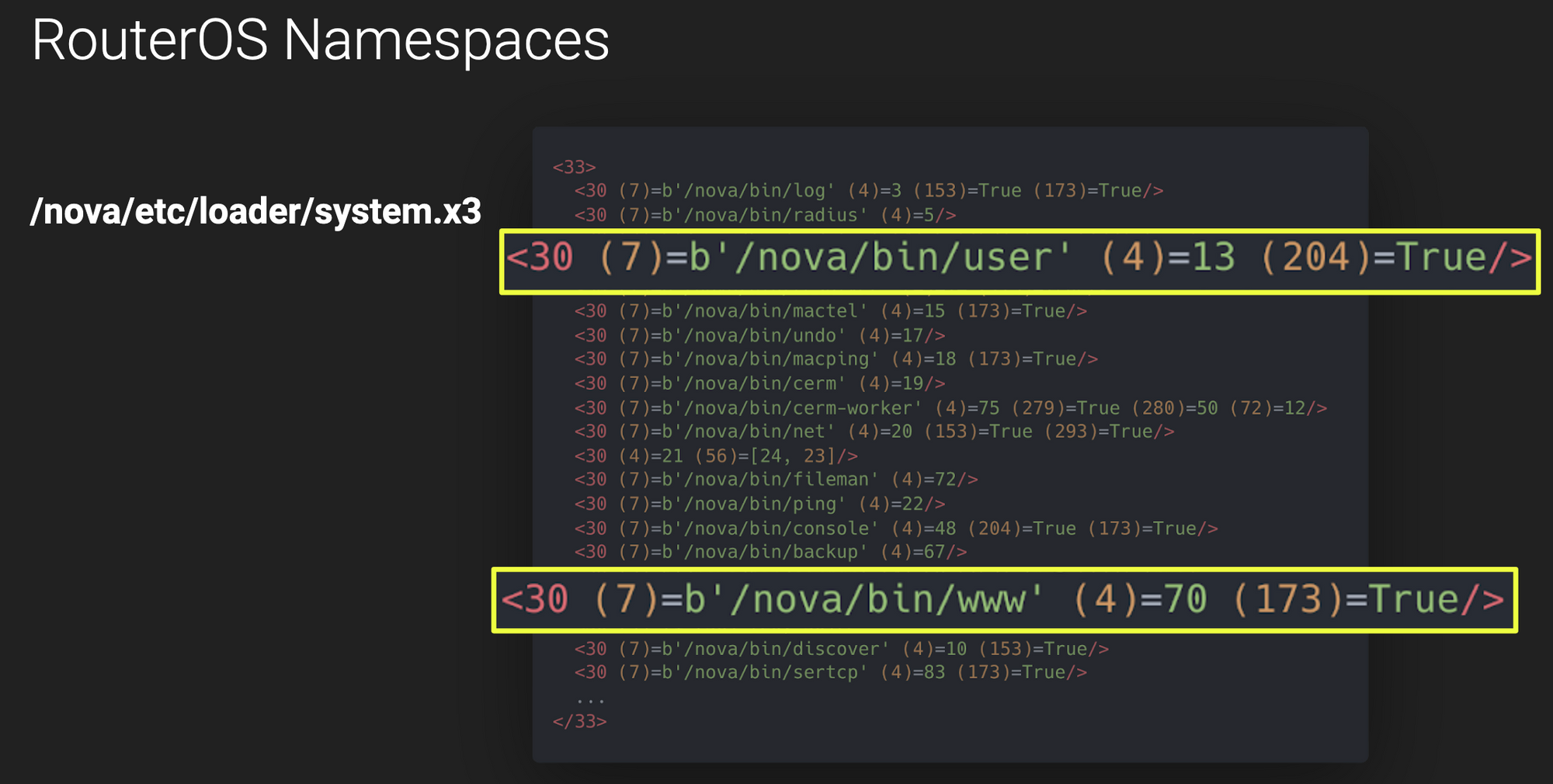

And now we can convert this serialized file into a more readable XML format:

Aha! Here we clearly see a list of process entries. And each entry has a parameter 7 which seems to correspond to the file path and a parameter 4 which must correspond to the RouterOS ID.

Nova Handlers

So that explains the 13 (user's ID), but what is the deal with the 4?

It turns out that RouterOS processes can register “Nova Handlers” (nv::Handler) which act as subsidiary components, capable of handling and responding to their own requests. In this case, we see that user registers several handlers in main, one of which is registered at index 4:

Neat!

It’s worth noting that every process also constructs a “Nova Looper” (nv::Looper) which acts at the interconnect between the process (e.g. /nova/bin/user) and the main controller (/nova/bin/loader). The Looper also contains a default handler, so if we were to send a message to address [13] (instead of [13,4]), for example, it would be handled by user’s Looper rather than a registered Handler.

IPC Message Routing

So this is cool and all, but how does it actually work? What actually happens when www exchanges a message? How does the message end up in user’s login handler?

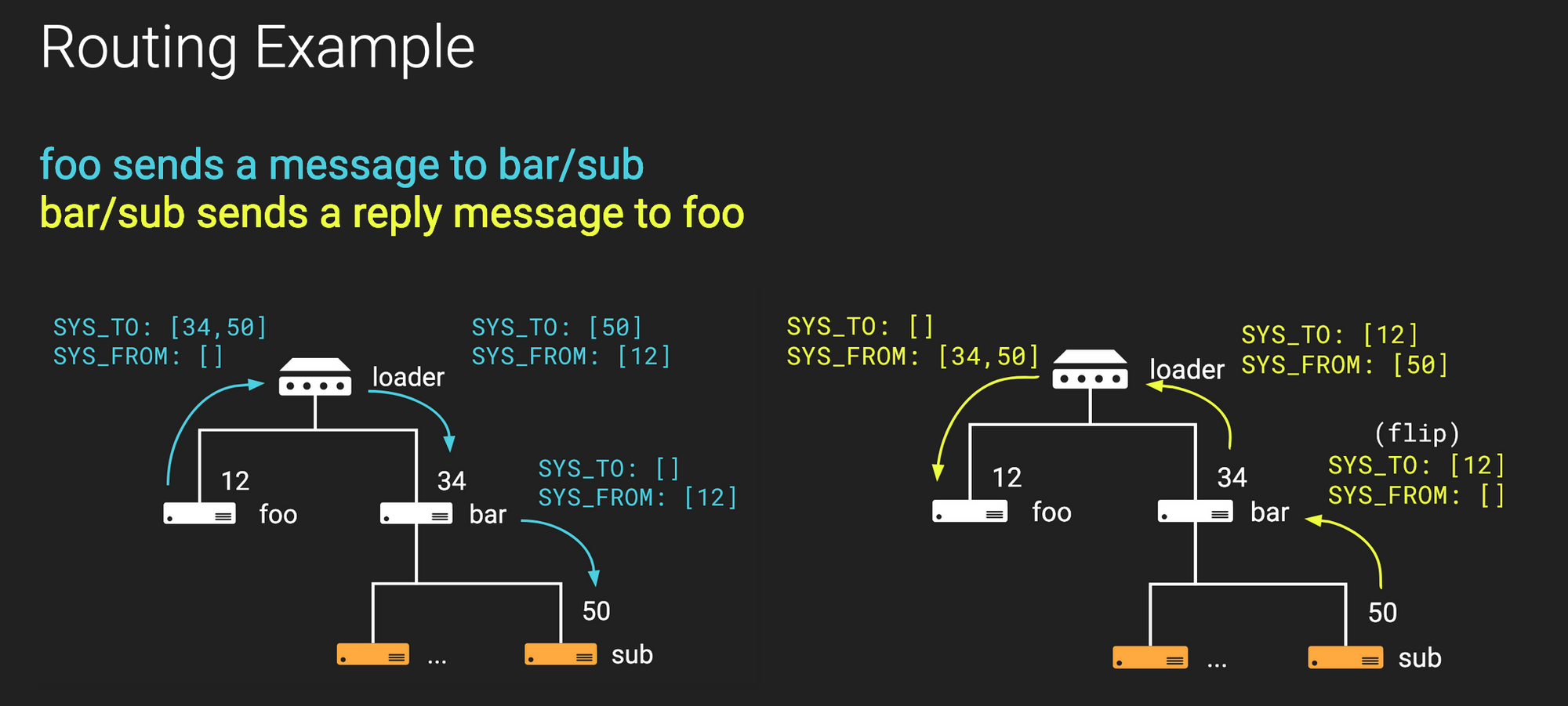

Let’s take a look at an example request and response. In this example, we have two processes: foo (at address 12) and bar (at address 34). Additionally, bar has a handler registered at address 50. In this example, foo sends a request to bar/sub and then bar/sub responds:

Request (in blue):

fooconstructs a message withSYS_TO=[34,50](bar/sub) andSYS_FROM=[]and invokesLooper.exchMessage()foo’sLooperforwards this message toloaderover a socket created whenloaderspawnedfooloaderreceives the message, determines it is fromfoobased on the receiving socket, and determines the destination isbar(based on the first entry inSYS_TO)loaderprepends12toSYS_FROM, strips34fromSYS_TO, and forwards the message over a socket connected tobarbar’sLooperreceives the message and, seeing thatSYS_TOis not empty, it locates a handler with address50bar’sLoopersuccessfully identifies thesubhandler, strips50fromSYS_TO, and forwards the message (in the same process) tobar/subbar/subreceives the message and, seeing thatSYS_TOis empty, handles the message directly

Response (in yellow):

- After

bar/subgenerates a response, it flips theSYS_TOandSYS_FROMlists in the original message. Now,SYS_TO=[12](foo) andSYS_FROM=[] bar/subpushes the message up to its parentLooperbar’sLooperreceives the message and identifies which handler sent it. In this case it isbar/sub, so it prepends50toSYS_FROMand forwards the message toLoaderover a pre-established socketloaderreceives the message, identifies the origin isbar(based on the incoming socket), and identifies the destination isfoo(based on the first entry inSYS_TO)loaderprepends34toSYS_FROMand strips the first entry fromSYS_TOand then forwards the message tofooover a socketfooreceives the message and, seeing asSYS_TOis empty, handles itfoo’sLooperidentifies this is a response to a previous request, prepares the return value, and returns execution tolooper.exchMessage()

This is a really cool way of routing messages and provides some useful features:

First, since SYS_FROM is constructed piece-by-piece as a message moves up the stack, this protocol protects against forgery; a binary or handler cannot spoof a source ID.

Secondly, loader is not just the hub of all process management, but also all message proxying. This means that loader is free to terminate services that are only intermittently needed (e.g., the user authentication binary) to free resources. If any services later require user authentication, loader receives a message destined for the now-terminated service and restarts it prior to proxying the message!

Finally, since message routing is performed dynamically, specific handlers can be refactored to other processes without much difficulty.

Multicast and Broadcast

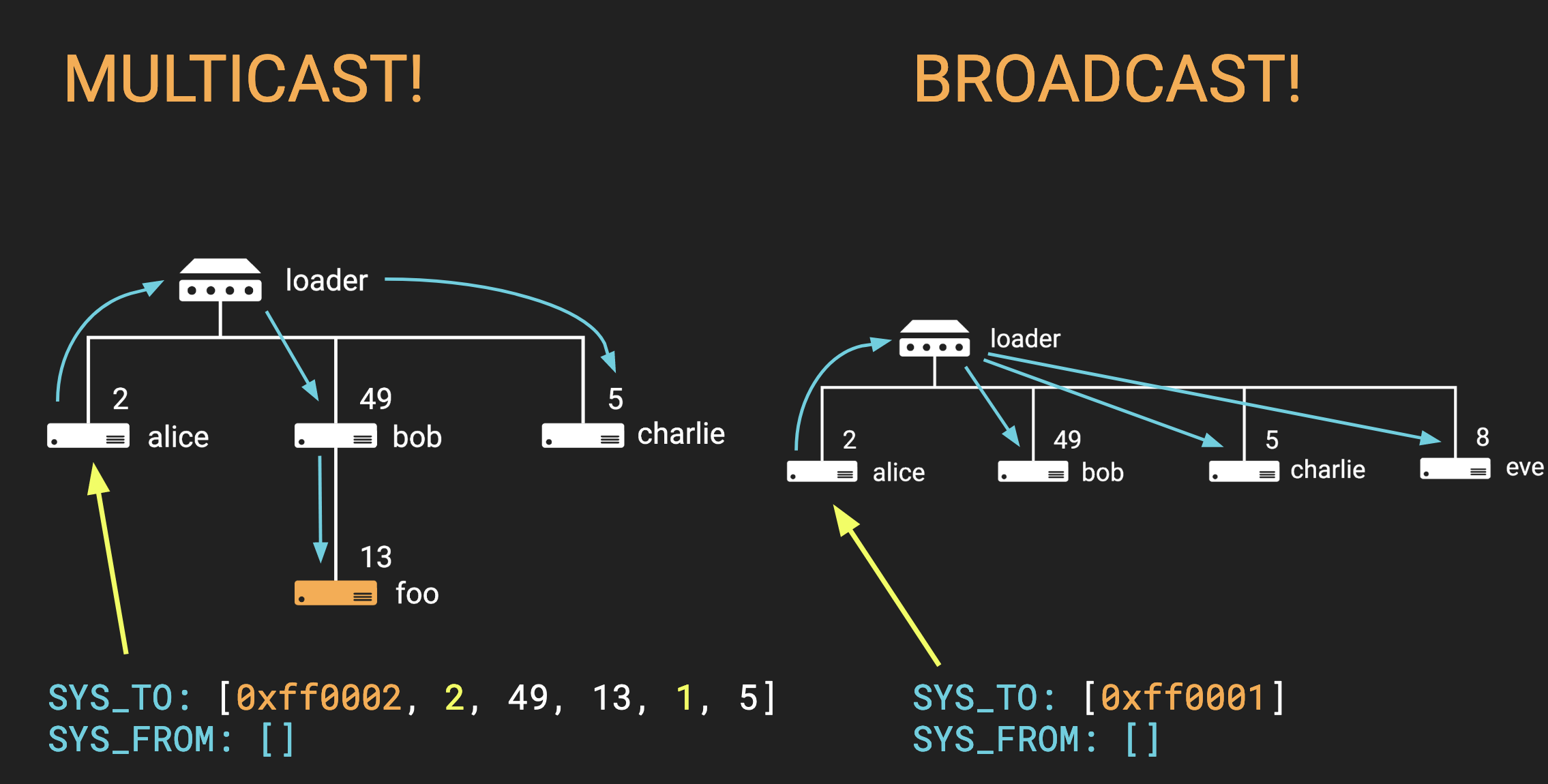

While most RouterOS messages are point-to-point (e.g. remote procedure calls or notification messages), RouterOS also provides functionality for multicast and broadcast.

A binary sends a multicast message by setting SYS_TO equal to [0xFF0002] followed by a list of targets. Or for a broadcast message, a binary simply sets SYS_TO equal to [0xFF0001]. Internally, loader parses these special formats and duplicates the message as necessary.

Hooking loader to Visualize IPC

Knowing all of these details, we wrote a tool to trace every internal RouterOS message. Because loader handles all messages, we need only sniff traffic passing through loader. Specifically, we proxy all messages from loader and forward them to a graphical front-end to visualize and decompose them. Included below is a demo of the tool. Notice that when we log in to the web interface there is a burst of authentication and data retrieval messages. Then, as we paginate through the web interface, we see additional requests for required data.

Hand-rolled Authentication

Security through Obscurity

Our next goal is to understand MikroTik's authentication scheme so that we can build configuration or research tooling that hits post-authorization endpoints. It is therefore time to talk about everyone's favorite topic: cryptographic protocols!

Initial investigation shows that the www binary, listening for web configuration traffic on port 80, uses a standard Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH) protocol to generate a shared secret over the Curve25519 elliptic curve, which is subsequently used to generate RC4 transfer and receive stream cipher keys.

That is all rather generic...too generic for the likes of MikroTik.

Thrillingly (or tragically, depending on your perspective), the mproxy binary listening for Winbox traffic on port 8291 seemingly does not use ECDH. Investigation of internal messages from mproxy to user shows a different series of data exchanged when compared against www’s authentication protocol.

In a rare stroke of luck, MikroTik’s wiki page details that Winbox uses “EC-SRP5” for authentication. Elliptic Curve Secure Remote Protocol (EC-SRP) is a rather obscure protocol, and the internet is fairly void of any good guides detailing its implementation. After a lot of digging through archives and cryptography guides, we find that the Wayback Machine holds the keys to the puzzle in the form of an IEEE submission draft from 2001.

To the best of our knowledge, this draft was never actually included as an IEEE standard, yet it is a great resource as it meticulously details EC-SRP's cryptographic calculations. Let's dive into it!

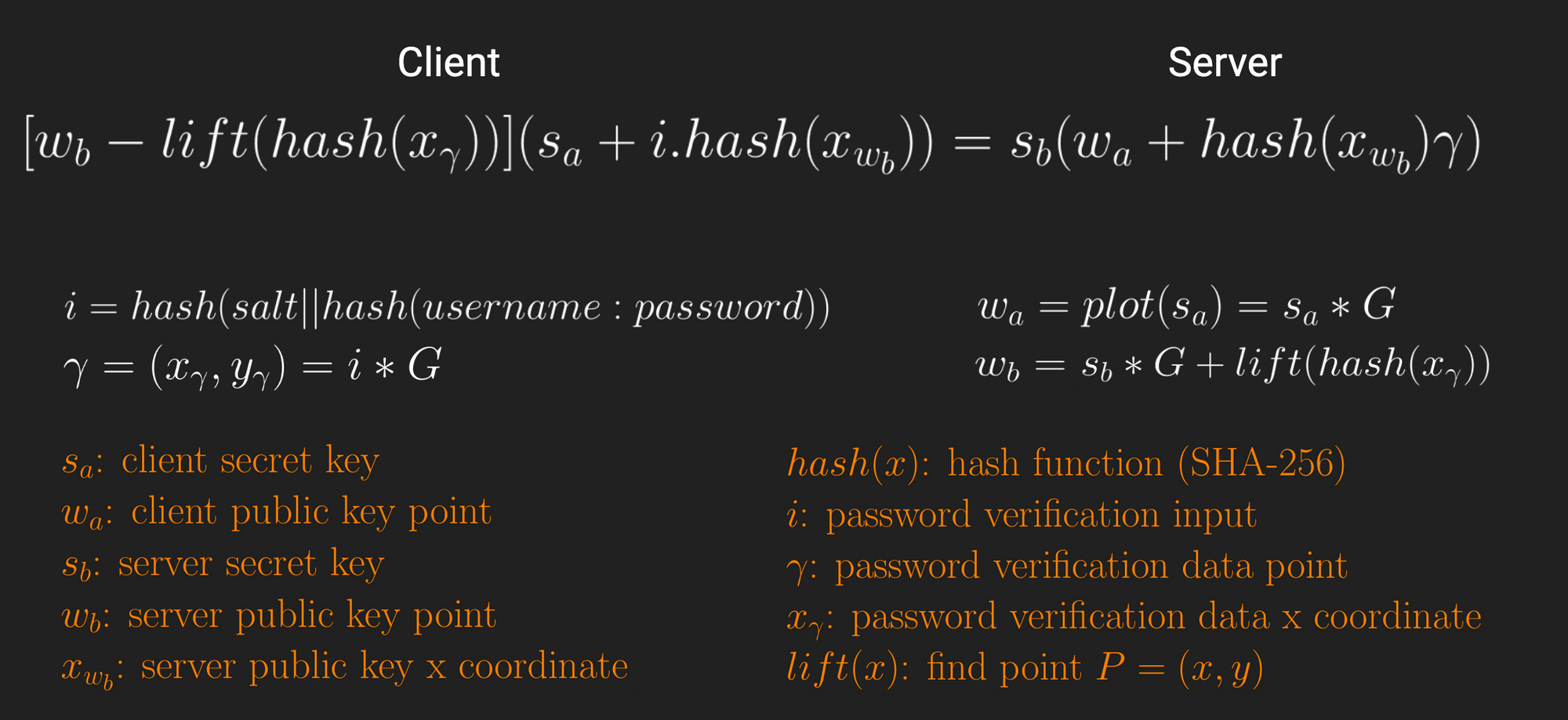

Ouch. That is a bit more complicated than ECDH. Let's break it down piece by piece so we are not overwhelmed.

Rationalizing the Differences

What we first notice is that this guide has some noticeable differences compared to the MikroTik implementation. Two major discrepancies jump out.

First, the guide makes no reference to the Montgomery (Curve25519) curve and all calculations are performed over the Weierstrass curve. However, with some extensive reverse engineering we find that RouterOS only converts Weierstrass curve points to Montgomery form right before public keys are shared, and it performs all elliptic curve math over the Weierstrass curve.

So we can abstract away that detail and focus on the math.

The second difference is that MikroTik seemingly performs more math operations under the hood, convoluting the high-level operations that the IEEE submission draft details. Dynamic reverse engineering shows us that elliptic curve calculations result in points with z coordinates, which is curious given the commonly defined Weierstrass equation is two-dimensional: Y2=X3+aX+b. With yet more research we find that MikroTik actually performs calculations using the projective Weierstrass form in three dimensions, y2=x3+axz4+bz6, and later projects the three dimensional point onto the plane Z=1 to convert back into two dimensions.

Again, this is an implementation detail that we can abstract away for the sake of our comparison.

With these two details out of the way, we can focus on a one-to-one comparison between MikroTik and IEEE submission draft operations.

Fingerprinting the Similarities...(or lack thereof)

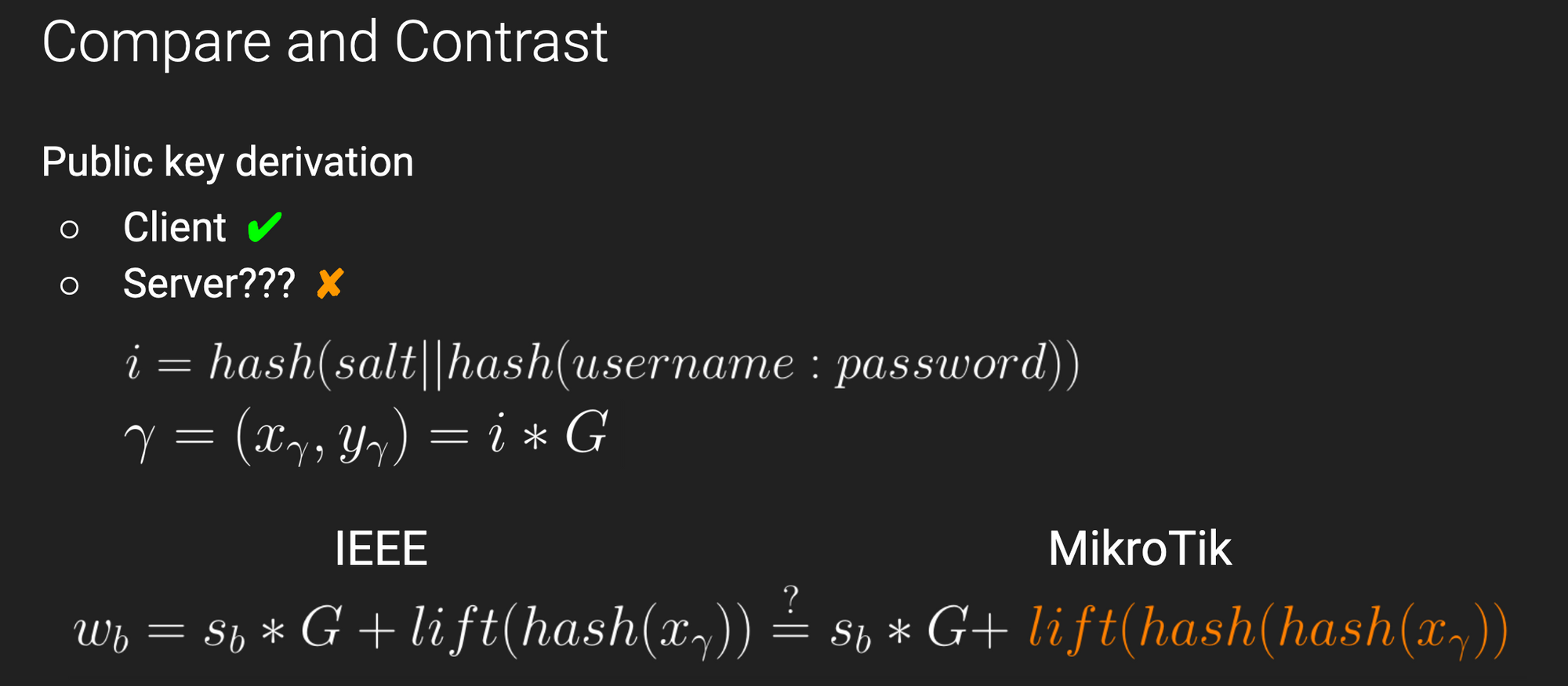

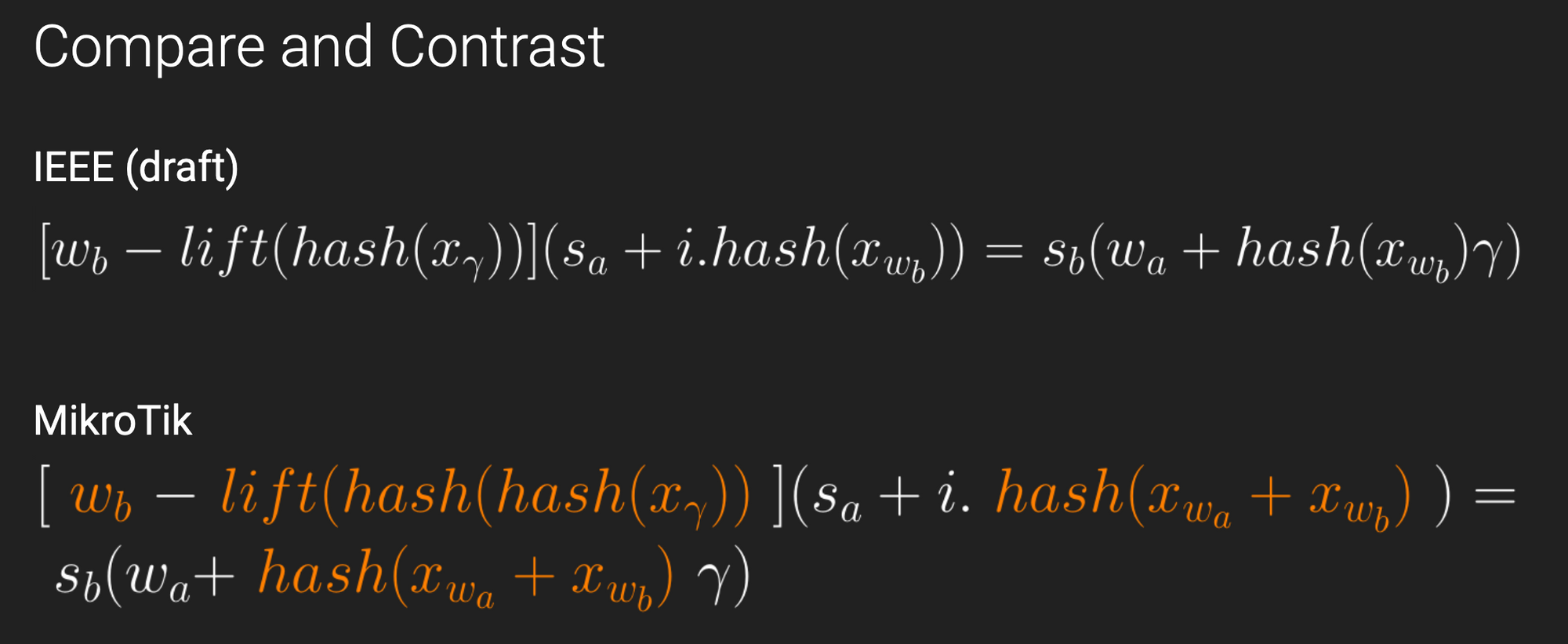

The first thing we notice is that the client public key calculation is identical, and also matches ECDH. The server public key calculation diverges from ECDH because it injects username and password information into the calculation to perform authentication during the key exchange. This is a feature of Password-Authenticated Key Exchanges (PAKEs), which is a core concept of all Secure Remote Protocols, including EC-SRP.

Unfortunately, when we compare MikroTik's server public key implementation against the draft, we find a significant difference: MikroTik hashes the x coordinate of a generated γ point twice, whereas the draft only hashes once.

This is concerning because hashes are, by definition, irreversible. The MikroTik client will consequently need to compensate when performing its calculation to account for this difference.

It is therefore unsurprising when we find that there are a number of differences in the MikroTik calculation, as shown below in orange, versus the IEEE submission draft. It is rather remarkable that, even with these alterations, the MikroTik server and client still successfully generate a mutual shared secret. Feel free to marvel at that realization, we surely did!

Finalizing the Protocol

There are a few final details required to successfully authenticate now that we have our shared secret. These include:

- Preparing and transmitting confirmation codes to confirm that both sides share the same secret. This also guarantees authentication, since an incorrect username or password would generate a wildly different point

- Generating AES-CBC and HMAC keys for tx and rx

- Implementing unique block padding for the AES cipher, which is almost-but-not-quite PKCS7

- Accounting for fragmented messages over 255 bytes in length

With those final details in place, we can now send encrypted messages and decrypt received messages from the MikroTik server!

Tools and Further Reading

If you are only interested in the final result, have no fear. We implemented a client version of Winbox and MAC Telnet (another common RouterOS configuration) service that you can plug-and-play. For those more interested in watching the authentication scheme progress, we also have a Winbox server implementation that can connect to the Winbox client. These tools are included in the first link below.

For those interested in the IEEE submission draft protocol, we created a client and server version of that protocol available in the second link.

Finally, we have additional details on the EC-SRP protocol and MikroTIk’s projective space calculations in a previous blog post, which you will find in the third link.

- MikroTik Authentication

- EC-SRP Authentication, as defined in the IEEE draft

- MikroTik Authentication Revealed

Jailbreaking RouterOS

Listening in on a Conversation between www...and Itself?

Let’s dive into a remote jailbreak we discovered in RouterOS! Our journey starts with the www binary which manages MikroTik’s WebFig web configuration portal exposed on port 80 by default.

After a bit of initial reverse engineering, we discover that www uses a servlet model to handle requests. This is a fairly common pattern for web servers and generally makes code nice and modular. Specifically, www registers certain url prefixes to servlets which implement the actual doGet, doPost, etc., methods.

For example, if we load /jsproxy/…, the jsproxy servlet handles these requests. Similarly if we load /scep/…, this request is handled by the scep servlet. You get the picture. In total there are seven of these custom servlets (not including the built-in servlets like dir).

Interestingly, the code for these servlets is actually separated into special .p shared libraries located in /nova/etc/www. For example, the code for the jsproxy servlet is located in /nova/etc/www/jsproxy.p.

In the spirit of conserving virtual memory, www utilizes lazy loading when dealing with servlets. www loads no servlets initially, and only upon the first request to a servlet is one actually loaded.

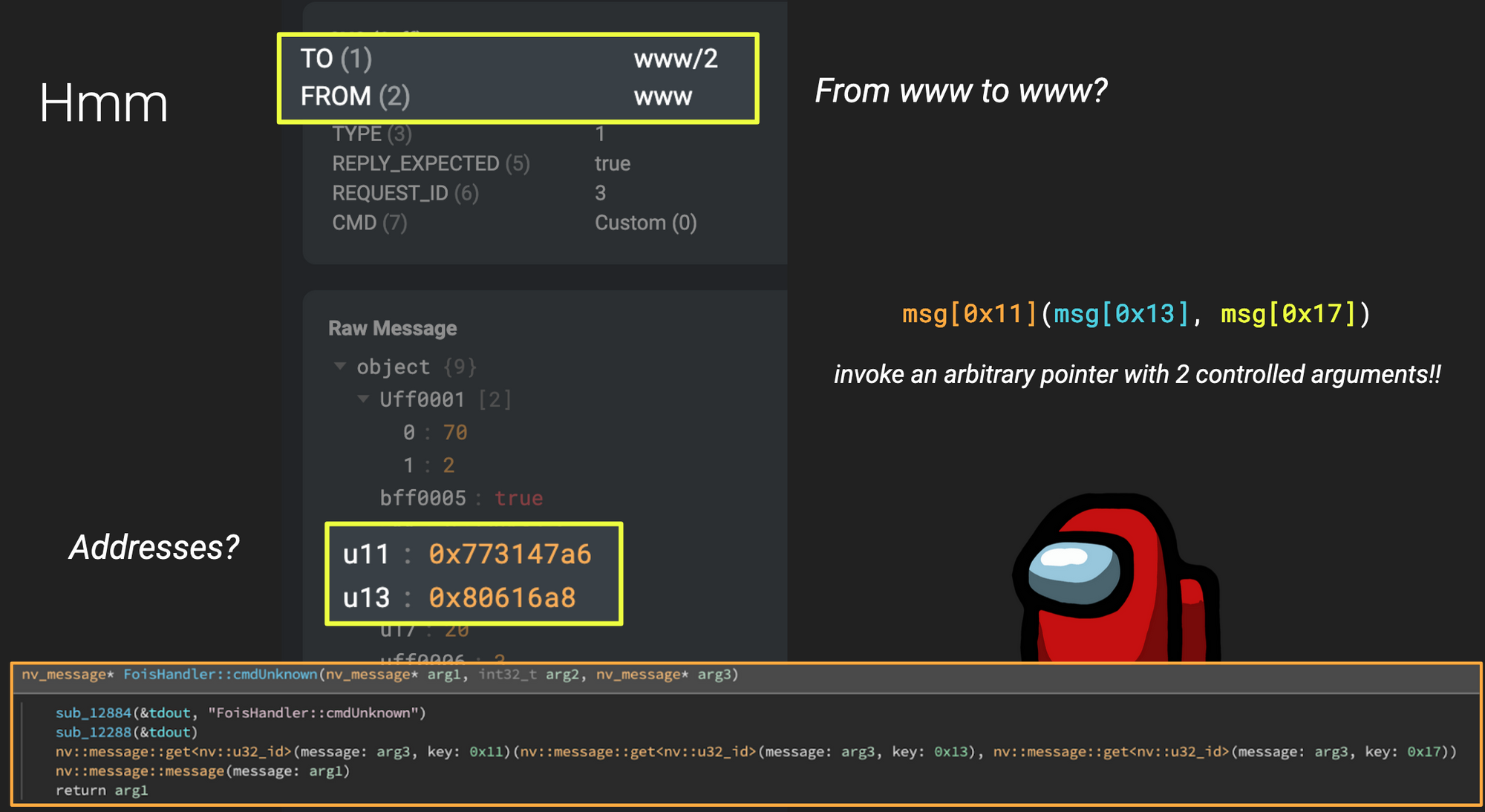

That seems like a pretty good model; but as we use the message tracer we noticed something interesting when a servlet is loaded. Specifically we see a strange message from www to www/2 (handler #2).

There are two things that caught our attention:

- Why is

wwwsending a message to itself? - Why do some of the values look like virtual addresses? (note: we’re looking at 32-bit x86 here). IPC messaging is for sending messages between processes, and virtual addresses should be meaningless

When we examine the handler for www/2 we see something even more frightening: it appears to pull a pointer from the message object and invoke it as a function?!?

It turns out that when a servlet is first loaded, it needs to register itself with the www process. And even though the servlet is loaded in the same process as www, the MikroTik developers decided to use IPC to perform this initial handshake rather than doing something more reasonable like having www look up any needed symbols in the servlet library…

Very spicy! If we could hit this handler with an arbitrary message, we could invoke any pointer and surely get a shell! But can we hit it?

Permission Escalation to super-admin

As an end-user, it is possible to send arbitrary messages into the system through one of the several proxy binaries, but we need to authenticate first. And since we already reverse-engineered the Winbox client as described in the previous section, all the hard authentication work is done! We can send arbitrary messages, but unfortunately hitting the handler is not quite that easy.

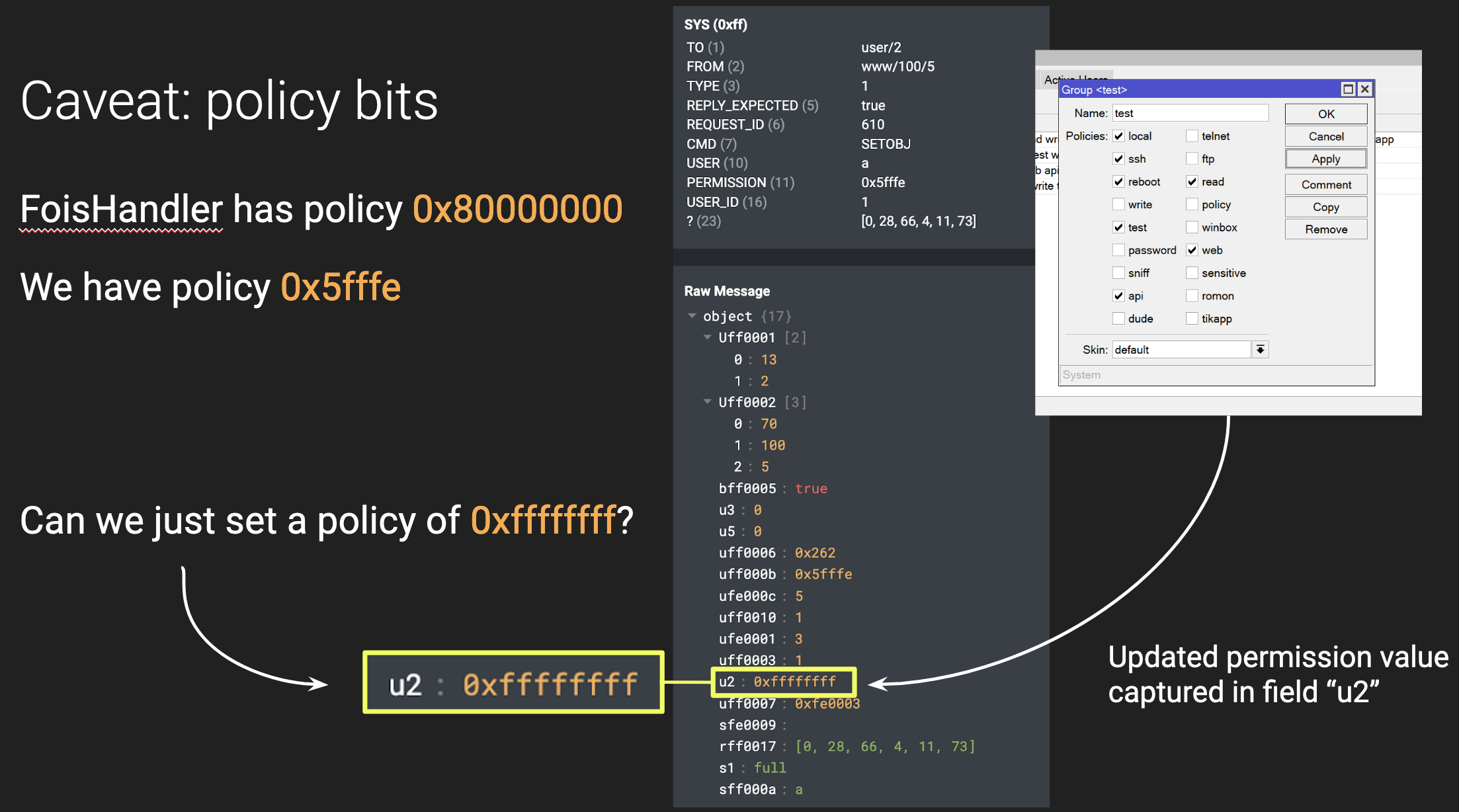

It turns out that RouterOS handlers are also gated based on a policy bitmask. In this case, our vulnerable handler www/2 (handler #2, FoisHandler) has a required policy of 0x80000000 which is unattainable via the GUI configuration panel. As an admin, our default policy bitmask is 0x5FFFE and the maximum we can set is 0x7FFFE.

Messages initiated internally have a maximum permission level by default, i.e., they run with super-admin privileges. But all of the messages we proxy through our Winbox client have their permission level set to something lower, which means we can never actually hit this handler with a proxied message.

Or can we?

The GUI controls policy levels with checkboxes that indicate certain privileges (e.g., read, write, ssh, reboot, etc). Using our message tracer, we see that internally this results in a single message sent with a combined bitmask value to indicate the permission level. The GUI will never send a message with a permission greater than 0x7FFFE, but what if we just send our own message with a permission of 0xFFFFFFFF?

This actually works and successfully upgrades our permission level from admin to super-admin, allowing us to hit the vulnerable handler!

ROPping and Popping

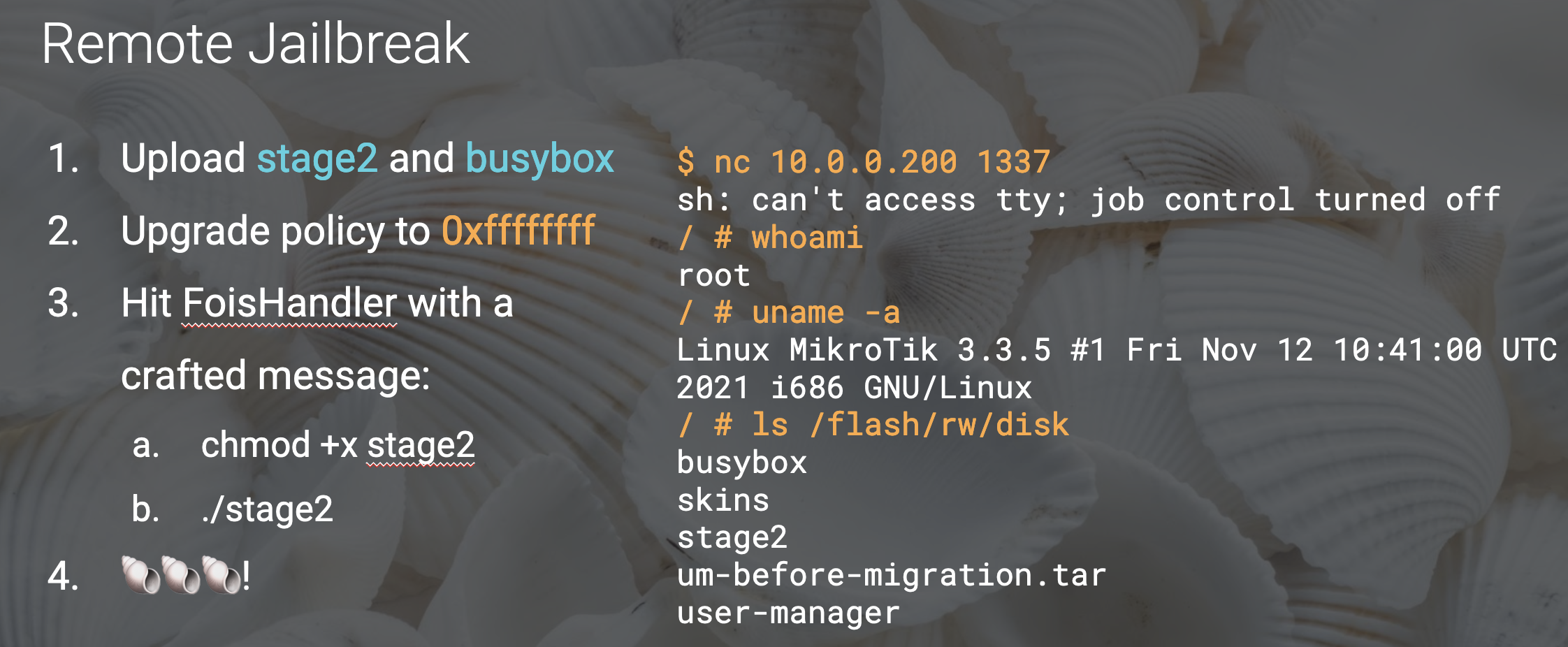

The last step is to achieve RCE, which we can do with the following steps:

- Upload a stage2 payload and busybox using FTP. The stage2 will execute a netcat listener using busybox and listen for traffic on port 1337. Because the exploit is post-authentication, we can use MikroTik’s FTP server to achieve this

- Send a crafted message to

userto escalate our privileges - Send a crafted message to FoisHandler, including a ROP chain in the body of our message which is stored on the stack

- Hijack PC using the controlled function pointer and pivot to the ROP chain

- ROP to

chmodto set our stage2 to executable - ROP to execute stage2

- Connect to the new reverse shell listening on port 1337

POC or GTFO

And just like that, we remotely jailbreak RouterOS for the first time in three years! It should be noted that this exploit is only viable on RouterOS v6, as FoisHandler was removed in the v7 overhaul.

Interested in trying it out? Our FOISted tool automatically jailbreaks RouterOS versions 6.34 (2016) to 6.49.6 (latest v6 release as of this post). Simply point it at your router's IP, provide credentials, and enjoy your shell!

Conclusion

This blog post covered a lot, so it is worth rehashing the knowledge you gained if you stuck with us:

- We now understand the construction of MikroTik firmware packages, and how to bypass cryptographic signing to get a developer shell on the RouterOS virtual machine

- We took a deep dive into the IPC message protocol, how messages are crafted, and how

loaderacts as the “router’s router” - We endured a chaotic adventure into EC-SRP5 as implemented by MikroTik for its Winbox and MAC Telnet services, and now have client programs that perform authentication on our behalf

- We added a novel jailbreak to our toolkit that exploits two post-authentication vulnerabilities to root any RouterOS v6 device, physical or virtual

Our intent for this post is to document these concepts and refresh the publicly available knowledge of MikroTik and RouterOS, with hopes of lowering the barrier to entry for other interested researchers and tinkerers. This is especially important because MikroTik gravitates towards obscurity, cluching tight to their hand-rolled source code and often leaving customer questions about implementation details unanswered.

You are now ready to start your own adventure into MikroTik research! Armed with this knowledge, together we can pull this target from the fringes of obscurity back into the limelight!

You can find the full slide deck for this presentation here.